Culinary influence of Lascar sailors

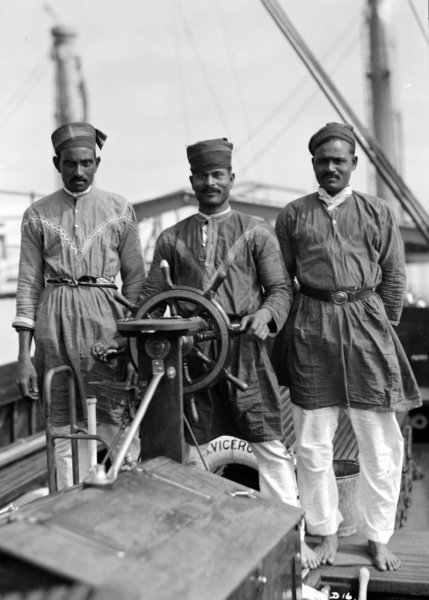

In the article, “Sailors, Tailors, Cooks, and Crooks: On Loanwords and Neglected Lives in Indian Ocean Ports,” Tom Hoogervorst writes about the culinary legacy of the Lascar sailors. The Lascar sailors were a group employed by the British East India Company beginning in the 17th century. Although originally the term described Indian sailors, eventually it came to refer to any non-European sailor including those of Asian, Arab, Cypriot, Chinese and East African descent. Lascars worked as seamen ranging from deckhands to firemen, but most importantly, as cooks aboard these ships and within trading communities across the British empire. Wherever Lascar cooks went, culinary landscapes mixed and developed. One mark of their legacy is the prevalence of loanwords from distant languages in these kitchens. For example, kabuli derives from the Persian “kābulī t̤aʻām” meaning “a meal from Kabul.” The well-known Indonesian dish nasi kabuli “Kabuli rice” thus reflects the Afghan dish of steamed rice-and-meat (kābulī pīlāv).

Hoogervorst explains how the two centuries of the East India Company’s operation were an intense period of culinary cross-fertilisation for the Indian Ocean. Hadrami, or Muslim South Indian cooks, brought with them the precursor to the savory flatbread known in Malaysia as murtabak. “Originally from Saudi Arabia and Yemen where it is known as muṭabbaq (meaning “folded”), in Kuwait this word usually refers to a dish of rice and fish (muṭabbaq) and in other parts of the Arabic World to a sweet pastry (muṭbaq). It was the meat-filled version that quickly conquered the Indonesian archipelago.”

Cities like Cape Town and Macau served as melting pots for influences spanning vast geographical distances. The cuisines in these parts of the world reflect unique hybridities and novel developments for dishes. In some instances, the diasporic cuisines may be all the more valuable:

Most of these historically connected words have diverged semantically over time, with dishes in the diaspora often differing significantly from what is known by the same name in the “motherland.” Some inherited recipes have blended with the cooking style of the recipient society, creating a “fusion” cuisine avant la lettre. It is equally possible that more archaic versions of a certain dish have disappeared everywhere but in the diaspora.

We highly recommend taking a deeper dive into Hoogervorst’s work as it presents a thorough study of interethnic contact in the Indian Ocean by way of cuisine, history, and linguistics. Find it here.