Portuguese influence in Asian food

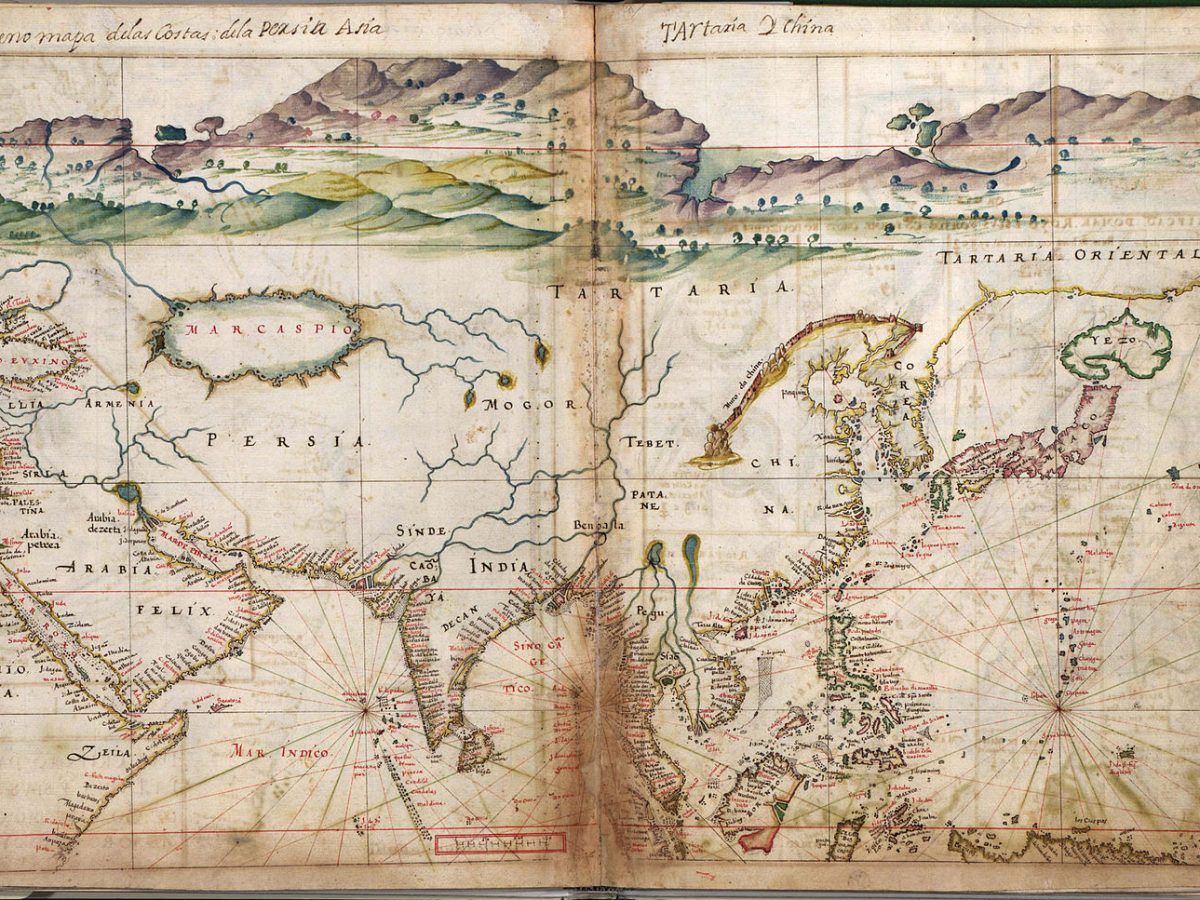

In her doctoral thesis, “A culinary history of the Portuguese Eurasians,” Janet P. Boileau tackles the narrative of the 15th century Portuguese sailors that inaugurated the era of European colonisation in Asia and created a creole Luso-Asian identity replete with unique foodways, customs, and a vibrant culture. Boileau suggests that the Portuguese were unusually receptive to two-way cultural exchange, unlike colonial powers that would come after. She credits their continued legacy in the region to this attitude. Large Luso-Asian communities continue to live in Cambodia, India, Macau, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Thailand to this day.

At Appetite, we are fascinated by this history as an exemplar case study of the development of a crossroads cuisine. Boileau traces the creolization of culinary traditions from Southern Europe with those of indigenous Asia. Boileau finds that “Luso-Asian dishes are characterised by a layering of ingredients and a complex blending of both flavourings and techniques. The Portuguese brought with them to Asia techniques for viticulture, distillation, oven-baking and yeasted doughs, sugarcane processing and sweet making. They also introduced Iberian cooking methods such as deep-frying, roasting (assado), stuffing (recheado), stewing (guisado) and steaming (bafado).” Boileau writes that Southeast Asians do not traditionally eat bread but adopted the habit of eating small breads, buns and pastries as snacks from the Portuguese. Pang susis buns and pastry-encased turnovers such as curry puffs and epuk-epuk descend from the Iberian empada.

On the other hand, the Portuguese developed a taste for Indian achar pickles, Chinese soy sauce, Yunan ham, and the salty sweet preserved olives called lám. The abundant use of vinegar and a preference for strong, tangy tastes came to define Luso-Asian cuisine. Rice, which made up the backbone of pre-colonial diets in Asia, remained central to the developing Luso-Asian diet. In a manner often characteristic of crossroad exchanges, we learn of the circuitous pattern of Arab influence on Luso-Asian foodways. Moorish introductions of fruit, spices, sweets, deep frying, vinegar marination, and household horticultural to Iberia would make their way to Luso-Asian communities with the Portuguese. Many of these culinary elements had already been introduced to Asia by Arab traders before Portuguese arrival, but the absence of restrictive food taboos in Portuguese culture allowed for culinary cross-fertilisation of a new scale. New World tomatoes and chillies would also come to feature prominently in this creole cuisine.

As Boileau acknowledges, her work is the first substantial investigation of Luso-Asian foodways and there are many unexplored avenues. We are excited by the prospect of digging yet deeper into the minutiae of crossroads and looking into the reverse flow of Asian contributions to Iberian cuisine. As Boileau makes clear, long after initial contact between societal groups, the resultant communities and identities demonstrate lasting permanence and what we might even call a hybrid vigor. As our work at Nouri shows, the crossroads of diverse histories and palettes inspires good food. Read the full book here.