RE-ENVISION: Renaissance European Cooking

RE-ENVISION is an ongoing series of research memos produced by our associates at Appetite. We trace the cultural genealogies of food from around the world to challenge commonly held beliefs about origin and authenticity.

The legacy of the Renaissance on food is no less significant than that on art, architecture, or music. Our study of the history of Renaissance European cooking uncovered some of the most important influences in contemporary culinary trends in the West. From accentuating class distinctions to the politics of slavery, the histories and stories of the Renaissance continue to live with us today.

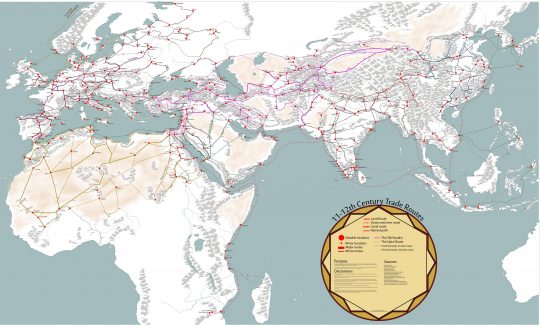

The map below details some of the major trade routes popular during the 11th and 12th centuries that were further expanded upon during the European Renaissance, which dates roughly 1300-1600.

1

1

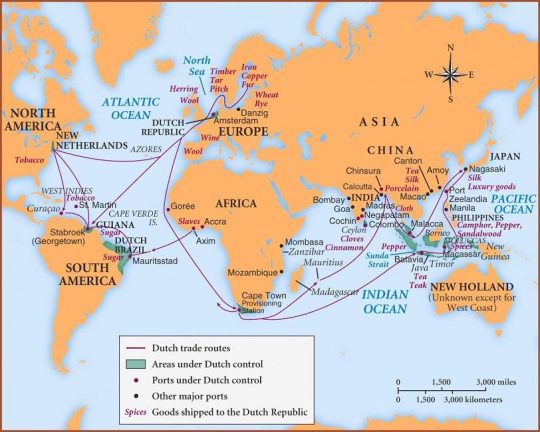

Mediterranean trade was dominated by the Italian monolith of Venice until the 16th century, when Ottoman expansion westward threatened the Venetian monopoly. Eventually, Portugal began trading with Asian empires for goods like spices and broke not only any vestiges of a singularly controlled Mediterranean, but of the Italian monopoly on the spice trade, too. This paved the way for others like Spain, France, England, and the Netherlands to access Asian markets. The “Age of Exploration” brought a whole host of new goods to be traded, including the trade of enslaved people from Africa. Germany and Italy began financing much of this trade through their extensive banking infrastructures.2 The primary trade routes and goods traded during this Age of Exploration are depicted in the map below.

3

Despite this expanded culinary access, diets were still highly stratified based on class. This was due to three primary factors: economic affordability, social and state policy, and cultural beliefs.

Peasants and lower classes ate far less meat than the upper classes, except on feast days where it was required by religious or state law. Meat was typically served one of two ways, either extremely fresh (killed just before dinner for extravagant effect) or salted and preserved. The latter was far more common. A majority of meat recipes from the Renaissance feature a heavily spiced stew to mask the foul taste and smell of the meat. The fresher meats were roasted over a spit and were more common for the upper classes. Whereas the spit was the preparation for the rich, the cauldron characterized the peasants’ meat preparation.

This stratification was also a result of state policy restricting access to hunting. Only the upper classes had the right to hunt game. Less extravagant meats like pigs and chicken were less regulated, but fowl (like peacocks, swans, and herons) were the most sought after for high class banquets and celebrations, and were largely inaccessible to the commoners.

Similarly, fresh fish was a luxury typically available only to the rich, and so was frequently salted and preserved for widespread consumption. The poor in port towns were an exception to the rule. Shellfish like oysters, crayfish, and mussels were considered dirtier and therefore fit for dockworkers, until the 17th century when oysters began to gain prestige and were consumed by upper classes as well.4 In 1563, Queen Elizabeth passed a law requiring everyone to eat fish on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. This was not a religious requirement but rather intended to support the struggling fishing industry. Violators of this law could face up to three months in jail. As a result, Elizabethan subjects began eating more fish and seafood than their European counterparts, regardless of class. Such staples included salmon, trout, eel, pike, and sturgeon, as well as crabs, lobsters, oysters, cockles, and mussels.5

Bread was known as the food of the poor, specifically cheap, whole grain breads like barley and rye. This kind of bread was less processed and therefore more gritty than the highly refined and sifted wheat-based white breads of the upper classes. Particularly illustrative of this disparity is the use of trenchers: stale bread cut into squares and used as a serving platter for food and sauces. When the rich were finished with their meal, the trenchers were given to the poor.

Aside from wealth, the other factors that contributed to culinary stratification were region and season. With limitations on refrigeration and preservation, most food would stay in a relatively localized region, with a few notable exceptions, like oranges expensively imported from Seville. Seasonally, many foods were only available for short periods of the time, or otherwise onerously preserved. Fruit, for example, was a luxury in its fresh state given the short window of ripeness. Otherwise, fruits were preserved in “wet” preparations, like marmalades, or “dry,” like preserved peels. These were the Renaissance equivalent of today’s candy sweets. Similarly, vegetables were preserved in brines or vinegars. Moreover, meat was seasonal due to the butchering seasons. Pigs were slaughtered in December, with much of the less-prime cuts preserved for springtime, and lamb was a welcome respite from the dwindling supply of preserved foods from late summer and early fall. Food festivals like Christmas and Easter that are still celebrated today illustrate this seasonal tension. Christmas is at the start of winter for the slaughter, and Easter in spring for the lambing. Lent is even conveniently located through the harshest winter months when there are few crops and game to be had.6

Overall, the stratification of food by class followed the widely believed principle that foods lower to the ground, like tubers, vegetables, and short animals (like chicken and pigs) were suitable for the poor while “higher” foods like fruit from trees, long-legged animals, and birds were the right of the rich. This led to a diet in which peasants ate many vegetables while the upper classes ate very few. Those that they did eat were “taller” foods like leafy greens. However, you could counteract the lowliness of a food with a food of a particularly high order; for example, it would be acceptable to serve pheasant with garlic at a lord’s table.7 Thus, a commoner during the Renaissance ate a diet much more reminiscent of what is today believed to be quite healthy. In the 16th century, however, this was not the belief. Dr. Baldassare Pisanelli of Bologna wrote in 1585 that “the rich man’s proper diet will sicken the poor man just as quickly as the poor man’s diet will cripple the noble. When peasants dine on birds, they get sick.”8

Most of the Renaissance beliefs surrounding the connections between food and health were holdovers from Medieval and Antiquity philosophy about the body’s four humours: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Foods were classified according to the humour it was believed that they influenced, and thus were prescribed to replenish or decrease humours to achieve balance. After the printing press was invented in 1440, diet books proliferated. These were mostly “courtly dietaries,” or books intended for courtiers with recipes and advice for eating habits at the lavish banquets they attended. It wasn’t until the 16th century that diet books began forbidding certain foods, mostly cakes and sweets, and warning against gluttony.9 However, much of these restrictions were based less on scientific reasoning than class structure. For example, as soon as sugar became widely available to the lower classes and was no longer an expensive luxury (in the mid-16th century), diet books began warning readers of the “adversities and sickness” it would engender. This is illustrative of a larger trend. Diet books were generally written for an upper class male audience; thus, foods that were popular among the poor were stigmatized, and foods deemed good or bad for women were only mentioned with regard to pregnancy or nursing.

Medical beliefs were furthermore influenced by cultural familiarity. During the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Europeans welcomed new spices, fruits, and vegetables from their new trade with the East. However, when the novelty of New World foodstuffs wore off, diet books began to warn against these new foods, too. New foods that had cultural analogues in Europe, like New World maize and European millet or barley, were easily accepted. But the potato and tomato were slower to gain wide acceptance – tomato vines are poisonous and Western Europe was slow to adopt the use of the tomato fruit.10 Staples of European cuisine like the tomato in Italy were originally feared and shunned from tables.

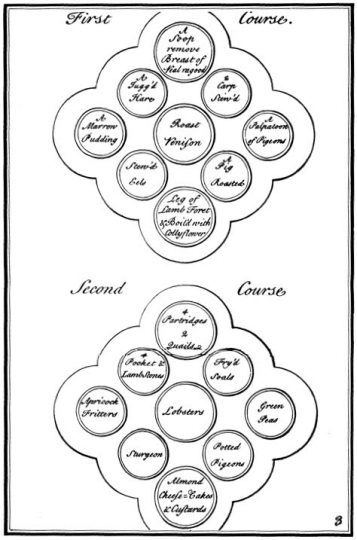

In addition to this plethora of new foods, the Renaissance also saw the widespread introduction of the coursed meal among the upper classes. In France, the entrée is more similar to what we now call an appetizer, a small introduction to a meal, and it first appeared there in 1555. Over time, a sequence of entrées began to develop, and in 1650 was more or less solidified in the following pattern: soup, then hot meat entrée, then the roast, and then a final course or “issue de table” (literally, exiting the table). In the 18th century, French and Colonial American banquet styles were standardized into two courses, each of which consisted of multiple dishes placed on the table in a prescribed hierarchy. The most important dishes, like the roast or pheasant, were placed in the middle, while soups or fish dishes were at the head, entrées scattered around the middle, and the smallest dishes (the hors d’oeuvres) were placed at the edges. Below is a map depicting how dishes were placed on the table in two courses in the French banquet style (à la Fraçaise) from Eliza Smith’s 1727 popular English cookbook, The Complete Housewife: or, Accomplished Gentlewoman’s Companion, the first cookbook published in the American colonies (in 1742). The “removes” refer to the practice of taking away the soup after its consumption and replacing it with another dish, the “remove.” These were typically fish, a joint, or a dish of veal.

11

The careful placement of these dishes was a method by which nobles could further emphasize their cooks’ “subletities” (in England) or “entremets” (in France). These were the presentations of foods as something else, constructed to look like castles or animals layered in gold leaf, or even other foods themselves. These grand shows of wealth and skill were valued for appearance, symbolic value, and rarity—often at the cost of taste. Even today, the fruit-shaped marzipans often consumed around Christmas are a vestige of this Renaissance tradition.12

By the turn of the 19th century, though, more upper class began leaving behind service à la française in favor of service à la russe (Russian style service). Whereas the French method consisted of the two buffet-like courses, à la russe had many more courses (usually 8 to 14), each one consisting of a single plate set before each diner. Cultural influencers like magazine writers, cookbook authors, and so-called “behavior” experts promoted this style to middle and upper-class women. Aside from the courses themselves, the primary difference between the two styles was in the presentation of the food itself—French style dishes were brought out in full, still in need of portioning, carving, and plating, whereas Russian style tables were bare except for the food on each diner’s plate and some decorative adornments.13

While today’s class-stratified diet may look different from that of the Renaissance, its legacy is enduring. Our culinary language, ritual, and behaviour have all been undoubtedly influenced by this era of creative flourishing. The Renaissance has given us many of our most popular and enduring culinary practices—from coursed dining to early musings on nutrition, but we must not forget that its history is equally founded on generations of oppression, subjugation, and exploitation.

It is through critical examination and the opening up of historical discourse, that we continue to shed light on the complexities of histories and the stories of our food and ways of eating.

Annotated Bibliography

“Food & Drink.” Accessed June 23, 2020. http://www.lepg.org/food.htm.

An in-depth look at foods and food practices in France during the Renaissance, this piece gives vital insight into the culinary class stratification of the era. It details factors like social policy that helped perpetuate such inequalities, as well as the role of season and region in both cultural practices and class distinction.

Jurafsky, Dan. “The Language of Food: Entrée.” The Language of Food (blog), August 25, 2009.

Dan Jurafsky is a linguist who studies the connection between food and language. In his analysis of the history and usage of the word entrée, he gives a correlate for the history of coursed meals, which rose in popularity during the Renaissance. Especially interesting is Jurafsky’s use of primary source material, like Eliza Smith’s cookbook, to discuss how language is put into practice, like the map of a coursed meal included in this piece.

King, Crystal. “Italian Renaissance Food.” Accessed June 24, 2020.

Author Crystal King’s work researching the food of the Italian Renaissance is especially helpful in parsing out the stratification of food based on class. King explains the widely held belief during the Renaissance that food lower to the ground was for lower classes, while taller foods high from the soil were for the wealthy. This is key in understanding the distinct diets of the upper and lower classes, and the “medical” prescriptions based upon this cultural theory.

Reeds, Karen. “Eating Right in the Renaissance (Review).” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79, no. 2 (2005): 326–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2005.0088.

In Karen Reeds’ review of Ken Albala’s book “Eating Right in the Renaissance,” she captures some of his primary observations about the connections between food and medicine during the Renaissance era. Reeds focuses especially on the role of diet books in influencing prescriptive food practices, as well as the role of cultural belief in affecting medical practice and advice.

“The History of Health Food, Part 2: Medieval and Renaissance Periods | Arts & Culture | Smithsonian Magazine.”

This article from the Smithsonian Magazine examines more closely the connection between food and medicine in Renaissance Europe. The article’s historical approach, drawing connections from the Medieval Era to the Renaissance, gives readers a better understanding of the process of classifying foods according to their impact on the body’s humours.

Central Coast Renaissance Festival. “What Did People Eat In Renaissance England?,” June 7, 2019. https://ccrenfaire.com/what-did-people-eat-in-renaissance-england/.

Written by Sofia Gardenswartz.

Notes

1Nick Routley, “A Fascinating Map of Medieval Trade Routes,” Visual Capitalist, May 24, 2018, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/medieval-trade-route-map/.

3“East India Co Trade Routes,” The Rigneys’ Great Adventure (blog), December 11, 2017, https://www.rigneyskandu.com/2017/12/11/indonesian-variety-by-bryce-2017/east-india-co-trade-routes/.

4“Food & Drink,” accessed June 23, 2020, http://www.lepg.org/food.htm.

5“What Did People Eat In Renaissance England?,” Central Coast Renaissance Festival (blog), June 7, 2019, https://ccrenfaire.com/what-did-people-eat-in-renaissance-england/.

6 “Food & Drink.”

7Crystal King, “Italian Renaissance Food,” accessed June 24, 2020, https://www.crystalking.com/thefoodofrenaissanceitaly.

8King.

9“The History of Health Food, Part 2: Medieval and Renaissance Periods | Arts & Culture | Smithsonian Magazine,” accessed June 24, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-history-of-health-food-part-2-medieval-and-renaissance-periods-70192474/.

10Karen Reeds, “Eating Right in the Renaissance (Review),” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79, no. 2 (2005): 326–27, https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2005.0088.

11Dan Jurafsky, “The Language of Food: Entrée,” The Language of Food (blog), August 25, 2009, https://languageoffood.blogspot.com/2009/08/entree.html.