RE-ENVISION: Sourdough

RE-ENVISION is an ongoing series of research memos produced by our associates at Appetite. We trace the cultural genealogies of food from around the world to challenge commonly held beliefs about origin and authenticity.

Over the last year, millions of people have had to look for creative and domestic ways to cope with the new normal of life indoors. Many people took up new hobbies like knitting, painting, playing instruments, and almost everybody tried their hand at baking. Temperature-sensitive and constantly shapeshifting, sourdough starters appeared in the kitchens of many new home bakers. Though it has been an international obsession for many years, sourdough’s history is far grander than we could have ever expected.

The modern use of the word “sourdough” refers broadly to leavened dough made from a mixture of flour and water. Naturally occurring microbes present in the air, wild yeast and lactobacillus ferment the dough and cause it to rise by trapping carbon dioxide bubbles inside. The result is a distinctly hard-crusted and tangy loaf of goodness.

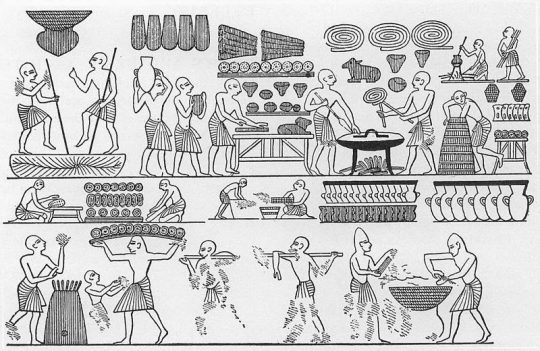

Archaeologists have been able to date remnants of sourdough back to about 4000 BC in Egypt, making it the first known civilization to make sourdough. Based on this discovery in Egypt, archaeologists believe that sourdough was first created when bread dough was left out in the open and wild yeast microbes naturally infiltrated the dough and caused it to rise.1 While the history of sourdough in Egypt is relatively well documented, its spread is far harder to trace. Evidence of leavened bread has been observed in Egypt by 4000 BC, Greece by 800 BC, and the Roman Empire and the rest of Europe by 150 CE, but there is a considerable gap in its subsequent history; the next commonly cited incidence of its spread is with Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World in the late 15th century. He is noted as bringing with him his own personal sourdough starter.

Part of this substantial gap in the record is likely a result of the difficulty of preserving bread for thousands of years as compared to non-perishables like the ceramic vessels in which Egyptians baked them. Second, bread is most often made with the intention of being eaten— and thus not saved— unless it is made for ceremonial reasons. As a result, much of the evidence of leavened bread comes from burial sites, where it is covered and protected by the burial process.

Additionally, there is little social and scientific consensus on what constitutes “bread.” While some purists only consider bread to be consistent with our modern day notion of leavened bread, others extend the title to a suite of unleavened foods like Mesoamerican tortillas and Southeast Asian roti. Because of these discrepancies, Andrea Heiss, in her 2017 research of bread remains in a site in Zürich, Switzerland, concludes that archaeologists should adopt a “standardised and structured laboratory protocol for analysing archaeological “bread” remains in order to allow for a general comparability of data from such finds.”2 In spite of this, it is without doubt that leavened bread has existed for thousands of years. Thus, its social and cultural significance throughout history cannot be overstated. Bread has, and continues to be, central to global food culture.

In the mid 19th century, sourdough became synonymous with San Franciscan culture. Sourdough played an integral role in the nourishment of pioneers during the Gold Rush, so they took careful measures to keep their starters— the fermented mixture of flour and water— alive and well. Pioneers would “feed” their starters daily by adding flour and water to make sure that the lactic and acetic acid microbes remained active. Caring for sourdough starters became so central to pioneer culture that Californian pioneers who migrated to Alaska for the Klondike Gold Rush even cuddled with their starters throughout cold nights in order to keep the microbes alive.3

Part of the fixation on sourdough from San Francisco was because it was considered to be the best in the world. In the 1970s, researchers Frank Sugihara and Leo Kine were determined to find out why. They discovered a type of lactic acid microbe present in San Francisco sourdough starters that was not catalogued anywhere else at the time. Thus, they believed it was unique to San Francisco, naming it lactobacillus sanfranciscensis. Since then, this species of microbe has been discovered in over 90 countries, yet the centrality of sourdough to San Francisco culture remains central. Although we cannot prove it with property, many people insist that San Franciscan sourdough is tartier, tangier, and tastier than anywhere else in the world.

Naturally leavened bread can be found all over the globe. In Egypt, there is aish merahrah, a mixture of fermented fenugreek and maize. In southern India, there is dosa, a pancake made from a fermented rice and lentil batter. In Italy, there is coppia ferrarese, a twisted sourdough made from flour, lard, salt, olive oil, and malt. In Iran, there is sangak, a whole wheat sourdough that is often made with poppy or sesame seeds. In Sudan, there is kisra, a fermented bread made from sorghum. In Ethiopia, there is injera, a fermented flatbread made using teff flour. Naturally leavened bread knows no borders.

However, not all naturally leavened breads use the same starter culture again and again like traditional sourdough does. The reusing of sourdough starter is unique because, if cared for properly, it can survive forever: shared and split infinite times. Sourdough starters are often passed down for generations, and some home bakers use starters that have been in their families for centuries. Boudin Bakery in San Francisco uses the same starter that Isidore Boudin began in 1849 in the thousands of loaves that they bake each day. Other bakeries will sometimes sell or trade parts of their starter cultures to aspiring home bakers.

Sourdough truly serves as a global symbol of generosity and history. Whether it belongs to you, your neighbor, your grandma, your friend, your friend’s uncle, your cousin’s friend’s great grandfather’s friend, or a stranger, sourdough starters symbolize an immense amount of effort and history all concentrated into a unique two-ingredient mixture. There are infinite variables to tweak when preparing sourdough: time, temperature, flour composition, wild yeast present in the air, number of backsloppings, and humidity. However, the innate complexity of sourdough all comes down to the interplay of two main ingredients: flour and water. It is no small feat that the relationship between these two ingredients has culminated in thousands of years of history and tradition.

Bibliography

De Guzman, Dianne. “Searching for Sourdough Starter in SF? Check the Telephone Pole”, SF Gate, April 4, 2020. https://www.sfgate.com/food/article/sourdough-starter-trades-neighborhood-SF-15175164.php

Eschner, Kat. “Gold Miners Kept Their Sourdough Starters Alive by Cuddling Them”, Smithsonian Magazine, March 31, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/gold-miners-kept-their-sourdough-starters-alive-cuddling-them-180962689/

Heiss, Andreas G., Ferran Antolin, Niels Bleicher, Christian Harb, Stefanie Jacomet, Marlu Kuehn, Elena Marinova, Hans-Peter Stika, and Soultana Maria Valamoti. “State of the (t)art; Analytical Approaches in the Investigation of Components and Production Traits of Archaeological Bread-like Objects, Applied to Two Finds from the Neolithic Lakeshore Settlement Parkhaus Opera (Zurich, Switzerland).” PLoS One 12, no. 8 (2017): E0182401.

Vail, Sharon. “Sourdough: More Than a Bread”, National Public Radio, September 12, 2006.

Written by Margot Richter

Notes

1Sharon Vail, “Sourdough: More Than a Bread”.

2Heiss, Andreas G et al. “State of the (t)art. Analytical approaches in the investigation of components and production traits of archaeological bread-like objects, applied to two finds from the Neolithic lakeshore settlement Parkhaus Opéra (Zürich, Switzerland).”

3Kat Eschner. “Gold Miners Kept Their Sourdough Starters Alive By Cuddling Them.”