RE-ENVISION: British Caribbean Food – A Culture of Abundance

By Frankie Jenner, with the Appetite Research Team

Introducing London

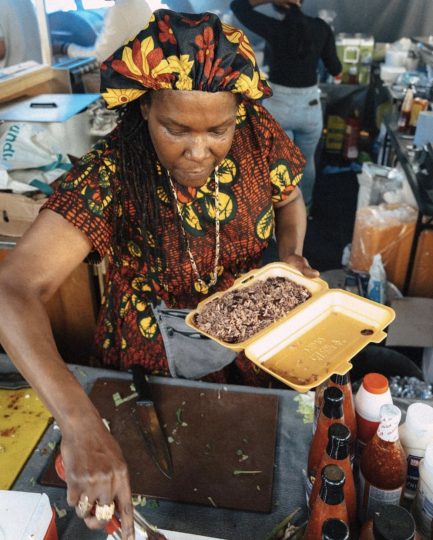

It is the first day of November and London is shrouded by the red and orange leaves that extend under its louring skyline. Commuters pack onto overcrowded double-decker buses and rest their heads against steamy windows as the rain batters the glass. I get off the number 1 bus at Waterloo and make my way to Millenium Park, a small green space nestled behind the train station, filled with wildflowers, sculptures and a woodland trail. Despite the weather, smoke billows from the far corner of the park, extending its aromas across the surrounding streets. If you follow the smoke’s trail to the source, you will find Jerk In Da Park, a Jamaican food stall run by Dionne and Prentis.1

Dionne has always been a caretaker for this park. It was established in the Millenium by a group of local residents and supported by the charity BOST ‘Bankside Open Spaces Trust’.2 Volunteers such as Dionne wanted to curate and nurture a space that would improve the health and wellbeing of urban communities. In a bid to raise funds for the charity, she began selling chicken under a tree on the other side of the park. The first day she came out, she recalls selling about three pieces of chicken. Prentis was not impressed. But Dionne was determined. It has now been just over fifteen years, and what started as a tupperware venture, has grown into one of the most iconic jerk stalls in London, attracting customers from all over the globe, enticed by the reviews that fill Tripadvisor, Google, Instagram, Facebook, exhorted by word of mouth and their acclaimed smell. ‘Our food is special’, declares Prentis.

Prentis was born in Victoria Jubilee Hospital in Kingston, Jamaica. He spent much of his childhood on this vibrant island and came over to England in his early twenties, where he met Dionne on the streets of Brixton …‘We are street people’ Prentis announced proudly. When I ask what food means within his culture, he tells me ‘food is personal.’ He recalls how he meditates on food, his ancestors imparting concepts for him to experiment with: ‘I create tings.’ In this respect, food is an integral part of Caribbean culture: it is a reflection of exchange, contact, collaboration.

Jerk In Da Park is one of London’s many Caribbean eateries. Such establishments have transformed, sustained and melded with this city. Their food offers us a lens through which to explore the relationship between Caribbean culture and London. Food is both offered and evoked. It is wrapped in banana leaves, sunk into deep bowls, cradled in fingertips, generously heaped onto paper plates at church Sunday potlucks and recalled through music and storytelling.

The arrival of Caribbean Communities in London

Caribbean communities have existed in London for centuries, but it was arguably after the Second World War that migrants from British colonies began to settle in the United Kingdom in higher numbers.

Post-war Caribbean migration to Britain is often referred to as ‘Windrush’. The influx of Caribbean migrants in the post-war period was due, in part, to the 1948 British Nationality Act that granted the status of ‘British Subjects’ to citizens of British Colonies. Shortly after, HMT Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury Dock in Essex, on the 21st June 1948. This heralded the start of large-scale immigration from the Caribbean to British shores.

Collectively, this swathe of Caribbean migrants became known as the Windrush Generation. Newspaper clippings and radio broadcasts across the island nations enticed many with the promise of jobs, a better life and more opportunities in the UK. The reality was to prove otherwise. Once they had disembarked from the Tilbury docks, many found themselves ostracised from society. Excluded from public spaces such as pubs, nightclubs and restaurants, they forged their own social spaces instead. Accounts of this period, such as Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners (1956) and Dread Beat an’ Blood (1975) by Linton Kwesi Johnson, capture both the romance and disenchantment of the city for its new citizens.3

‘Windrush’

by Roger Robinson

They came down from the ship

on a footbridge of firewood,

architectural pleats in their trousers

and suitcases each containing a live lizard.

Eventually they’d put away

their bowties of cut banana leaves

and take to drinking sea-water shots down

the pub with beards of black smoke.

On the weekend they’d play bingo with passport

pages and levitate at late night to basslines in the Mecca ballroom.

They’d eat their fried clay dumpling and salted

shark and don hat brims so sharp it could cut style,

with their twopence coin-button, double-breasted

jackets with pocket squares of betting slips.

But still the three wooden birds on their walls

were flying back home in super slow motion,

because nothing promised was what it seemed,

but it was somehow more than what they left.

Roger Robinson, ‘Windrush’ in A Portable Paradise (2019)

Roger Robinson captures this dichotomy, between romance and disenchantment, in the last stanza of his poem ‘Windrush’.4 Robinson is one of the most important voices in contemporary black British and Caribbean poetry, whose work often speaks to the spirit of places, of home and comfort. In his distinguished collection of work, A Portable Paradise (2019), Robinson crafts a rich and insightful tapestry of the black British experience, one that is unique to post-Windrush generations. The poem is punctuated with references to food, drink and music; banana leaves, sea-water shots, pubs, the late night basslines of the North London dance hall, Mecca ballroom, fried clay dumplings and salted shark. It conjures the sensory landscape that many Caribbeans faced when they embarked from ships at the Tilbury Docks.

Defining British Caribbean

Photographer Johny Pitts and poet Roger Robinson produced a document of Black Britain in their recent publication Home Is Not A Place (2022).5 The project seeks out a blackness that exists outside the mainstream news and trending hashtags. It pours over the everyday humanity of blackness in Britain. The confluence of poetry and photography explores the history of Empire that every Briton is bound to; the negotiation of arrival, asylum, refuge, deportation and departure, across the geographies of Europe, Africa, America and the Caribbean. In a reflection of the book, Pitts remarks that Blackness, not to mention the concept of Britishness, is inherently complex because of this.6

Defining ‘Caribbean’ and ‘British Caribbean’ is therefore a complex task to navigate. It involves having to define countries across a vast geographical region with disparate languages, dialects, religions, ethnicities, soil makeup, tropical climates, and ultimately … cuisines. The Caribbean encompasses thirteen sovereign island nations and twelve dependent territories over a distance of approximately one million square miles. In his book, Belly Full (2017), Riaz Phillips expresses the difficulties of defining ‘Caribbean’ as pertinent to those from far afield, just as much as its native residents.7

What is recognised as Caribbean food in the UK, is largely informed by the dominant presence of those descending from English-speaking Caribbean islands, most notably, those of Jamaican heritage. Following the wave of migration during the Windrush period, many people from other islands, such as Antigua, Barbados and Trinidad, found they were generically categorised as either ‘Jamaican’ or ‘African’. Caribbean settlers were assimilated as one people. Jamaican cuisine has therefore taken the centre stage of Caribbean cuisine in many Western regions. Phillips makes the point that ‘Caribbean food in the UK thus appears to be a collective or assumed identity of the English-speaking Caribbean Islands’.8

I had the honour of speaking to the co-author of Home Is Not A Place, Roger Robinson, to learn more about British Caribbean food cultures. Robinson was born in Hackney to Trinidadian parents. He spent much of his childhood in Trinidad and returned to London when he was eighteen. Robinson tells me how a lot of British Caribbean eateries market themselves as Jamaican, but in reality are actually a smaller island, such as St Lucia: ‘It’s really interesting how you would advertise the bigger, more popular country, even though you are from a smaller island.’ Jamaican cuisine has taken centre stage in Britain’s perception of Caribbean cuisine.

The Evolution of British Caribbean Food Culture

For many Windrush settlers, memories of the Caribbean lived on in food and music. Early to mid-20th century Britain provided little access to re-create the paraphernalia of their memories. Many food vendors did not offer basic Afro-Caribbean produce, such as plantain, yams, soursop, dasheen and green bananas. Transport was slow and therefore produce would often arrive expired, mouldy and rotten. Likewise, staples such as rice were not readily available, the only rice available was that used for making rice pudding, a much starchier grain.9 Transport links between Britain and the Caribbean improved, and by the late 1970s, many businesses were able to source and import more produce from major Caribbean brands, such as Grace Kennedy.10

The sound systems of Kingston, Jamaica, filled the basements of houses, blasting Ska and Reggae, accompanied by plates piled high with rice & peas, curried meats, fried dumplings and cups filled with rum and coke. This lively underground network bubbled over onto the streets, creating the foundations for annual celebrations that are still marked today, such as Notting Hill Carnival. Phillips describes this sensual landscape as consisting of ‘makeshift steel barrel Jerk drums, Trinidadian rotis being made out of the back of cars and Caribbean kitchens being recreated out of the back of vans and car boots’.11

Street-side food offerings found more permanent spaces inside eat-in establishments and regular street vendors. Not only were they able to supply jobs to members of their immediate communities, but they also became places of congregation for the larger migrant diaspora. The first notable wave of such eateries began appearing in the late 1960s: places such as the former Mangrove Restaurant in Notting Hill, West London, R&JJ West Indian in Hackney, East London and Dougie’s Hideaway Club and West Indian Restaurant in North London.12 Deprived areas such as Notting Hill were witness to a precarious flame of civil unrest, one that fuelled race riots, like those in the summer of 1958. But the city was also ignited by a different kind of flame: one that grilled plantain, smoked jerk marinated meats, warmed the underside of a flaky roti and simmered the surface of a fish curry.

When I ask Robinson how British Caribbean culture is evoked through food, he recalls fond memories of selling West Indian food at carnival each year. His friend owned a restaurant and managed to obtain a licence to sell food out the back of his van during the weekend of celebrations. For Robinson, he remembers this as a real experience of West Indian food in Britain; carnival goers wanted to stir up the memory of an island that their ancestors belonged to or one they had visited, as many were no longer first generation, they tried to summon these connections through vibrant sound systems and plates piled high with nostalgia.

Phillips and Robinson demonstrate how deeply food and music are intertwined when we talk about the evolution of British Caribbean culture. We cannot access smell or taste without first hearing the beat of the Caribbean sound systems. Londoners would dance the night away at blues parties and ‘levitate at late night to basslines in the Mecca ballroom’ whose healing frequencies Robinson reminisces over in ‘Windrush’.13 Hungry souls would then find comfort and nourishment in Caribbean food served out the back of cars and vans, many forged deals with club and pub owners to cook in and around these premises, such as The Fridge nightclub in Brixton, South London and the Ridley Arms in Dalston, East London. Robinson tells me about a distinctive memory he has of eating steaming hot, red pea soup with hand rolled dumplings outside The Fridge at one o’clock in the morning during the early nineties. He remembers being freezing and thinking: ‘Wow … this really is the black British experience.’

How British Caribbean Food Cultures Sustain the City

It is this culture of celebration and generosity that sustains this city, a city that is so often consuming itself. This is a concept that the architecture critic Rowan Moore echoed in his 2015 article ‘London: the city that ate itself.’ The city is depicted as a land ruled by money, ‘whereby anything distinctive is converted into property value’.14 In Jonathun Nunn’s latest publication, London Feeds Itself (2022), he too describes a city that is consumed by its own greed:

‘Working class markets are shut, replaced with cookie-cutter street food placed on pseudo-public property; where food production is being shunted to its peripheries or out of the city altogether; where community centres are shutting and food banks are rising; where new restaurants open just to be a notch in the landlord’s bedpost.’ 15

Urban areas are reduced to ash in the name of ‘renewal’, ‘regeneration’ and ‘redevelopment’. The parasitic attack of gentrification attaches itself to oat flat whites, Franco Manca sourdough pizza boxes, and Planet Organic superfood health stores. Nunn acknowledges these patterns, but also offers an opposing vision, one that acknowledges the generosity and abundance of the city.

‘London feeds itself […] in its warehouses, parks, church halls, mosques, community centres, and even its baths.’ 16

Jerk In Da Park is the perfect evocation of this sentiment. Monday through Friday, Dionne and Prentis begin preparing food at 5am: ‘This food take time to cook’, Prentis tells me. Loyal customers queue as the sun rises, marking the end of their night shift; paramedics from the London Ambulance service headquarters, nurses from nearby St Thomas’ Hospital and security guards from the office blocks that surround the park. Once key workers have been fed, then come the mid morning crowd, on their way to work; trainline staff heading for Waterloo station and then the nine to fives seek out their lunchtime fix. Towards the end of the day, Dionne and Prentis feed the homeless community that congregate in the park. Any leftovers are given to them, nothing is wasted.

When talking about what food he likes to cook, Robinson proclaims ‘I like to cook food that makes everybody feel happy. It’s not nouveau cuisine, it’s big portions, plenty of food, tasty, a lot.’ This theme of abundance is proclaimed once again in these portion sizes. Dionne, Prentis and Robinson all speak to the possibility that someone may drop by: ‘even though people aren’t used to the idea of dropping by, people used to drop by,’ says Robinson. Prentis recalls his childhood in Jamaica, where each evening, all his family members would cook and send it to one another across the island; likewise, every Sunday, Dionne, her mother and aunt send food back and forth over London.

‘It’s like a handshake’

Food serves as the glue that binds together an extended network of family, friends and strangers. It is abundant, generous, it marks a celebration, it brings people together and raises them up. Robinson perfectly encapsulates this sentiment: ‘It’s like a handshake.’

London’s Caribbean communities have tirelessly fed themselves and the city at large. The culinary backbone of this city does not sit with the brand-name chefs and their restaurants, nor does it nestle within the elite postcodes of Mayfair and Westminster. Instead, it stands defiantly in the, typically unsung, food of immigrants and their extended families. It is in these kitchens that we can really learn about the life of the city. Memories live in the sizzle of hot oil, tales of hardship rub off from hands as patties are formed, and comfort is found in the nooks and crannies between stacks of tins in the cupboard.

Food as Culture

Not only do these memories reflect the centuries-long, fraught colonial relationship between Britain and the Caribbean, but also the more extensive stories of migration, assimilation and celebration that each island nation has to tell.

When talking to Dionne, Prentis and Robinson, all three mentioned the impact of the Chinese diaspora in both Jamaica and Trinidad. This observation reflects the influx of Chinese migrants to the Caribbean islands in 1854 after slavery was legally abolished. Many of these migrant workers were fleeing from opium wars, political unrest and widespread hunger: their migration must not be perceived as a ‘choice’, many were abducted and forced to sign labour contracts. Once they arrived on Caribbean shores, they replaced the unpaid labour of indentured Afro-Caribbean enslaved peoples. Subsequent waves of migration followed throughout the twentieth century, and by 1970 there were just over eleven-thousand people of Chinese descent living in Jamaica alone.17

For Prentis, the impact of the Chinese-Jamaican diaspora runs deep: that’s where the origins of his street name lie. He was given the name by the Chinese in Spanish Town in St. Catherine, Jamaica. His earliest memories of cooking are also deeply tied to this vibrant community. He tells me his grandparents taught him how to season but he learnt the rest from the Chinese, out of a restaurant kitchen on Oxford Road that operated night and day.

When we think about British Caribbean food cultures, it is a story of diasporic offerings: created by their ancestors, a mix of traditional West African cuisines from countries such as Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone; informed by their time of forced servitude under British, French, Portuguese, Dutch and Spanish colonialism; and then adapted by the communities that migrated such as Chinese, Indian and Jewish. Each fraught relationship introduced a swathe of new ingredients, cooking techniques, recipes, styles and methods of eating. Robinson notes the unwavering presence of a wok in a Trinidadian kitchen and the unspoken rule that savoury Jamaican dishes have the underlying sweet aroma of spring onions, a staple ingredient in a Chinese kitchen.

Britain has ingested this culture, one that is continually evolving, splintering and being reformulated. Robinson speaks fondly of a Trinidadian spot near Arsenal, North London, and how the owner is taking traditional Trinidadian food and ‘morphing it’. He recalls one reworking of the pastelle. Because of Trinidad’s proximity to Venezuela, the pastelle is Trinidad’s equivalent of a meat-filled arepa. It is often made with minced beef, olives and raisins, savoury with hints of sweetness, piled into a corn-filled crescent and then boiled to make a kind of corn meat pie. This North London eatery has taken the pastelle and made it with goat meat, which Robinson says would never happen in Trinidad, ‘that kind of twisting traditions is mad’, he says. This is just one example of how the British Caribbean community here in London are creating their own culture, one that is always evolving from that forged by their ancestors.

In his newsletter, Vittles, Nunn argues that it is important to remember that whilst these developments in Caribbean food are happening in Britain, and therefore are products of British history, they are not Britain’s to stake a claim over. He describes Britain’s influence on Caribbean food as ‘more perverse, but ultimately stronger’, through the movement of bodies, the forced movement of enslaved peoples and indentured labourers and the promoted movement of ‘British subjects’.19 But what Nunn overlooks is how history repeatedly reveals that to be ‘British’ is to stake claim over what is not ‘Britains’: we only have to look to the history of the British Empire to understand this.

‘The Caribbean food of the UK is not Britain’s to claim but it is British history.’ – Jonathan Nunn, Vittles.

At Appetite, Chef Ivan remarked that Caribbean food in London appears to be ‘very British’, perhaps even more so than fish and chips. This may well be the case, especially when we consider that the majority of Jerk In Da Park’s customers are white. But we must understand that to be ‘British’ is an inherent contradiction. To be British is to be at a crossroad. It is to find oneself in what you believe to be the centre of an intersection, but as time passes, you realise you constitute one crossroad in a larger web of complex mazes. This is a subtle nod to the perceived centrism of the British Empire, its presentation of its ever-more glorious past, and its ultimate demise, forceful takedown and fall: the realisation that the world is larger and more powerful than its colonial rule. This crossroad is built on the back of enslaved people. It is built on exploitation: through the structures of racism, and colonialism. This crossroad therefore serves as a framework that we can use to understand the concept of ‘Britishness’. To be ‘British’ is to be situated within this crossroad: a white history, a black history, a brown history: a confluence and weaving of these histories. To be ‘British’ is to be a creator, an upholder, a by-product or a victim of these histories: often a complex combination of several of these. It is within this crossroad that we must understand the complexity of British Caribbean food.

The history of British Caribbean food must be understood amidst the weight of its ‘Britishness’, but it must also be celebrated with the voices of those who are reclaiming, experimenting, developing and sharing this culture. Prentis tells me, ‘I stand here, as a Jamaican, as a black man, and I tell you that ninety-percent of our customers are white.’ Himself and Dionne tell me how proud they are that Jerk In Da Park is able to offer people from all nations a way to take part in their culture, through food.

In Ligaya Mishan’s essay on ‘Asian-American Cuisine’s Rise, and Triumph’ for The New York Times, she speaks about a ‘new American palette’ that welcomes Asian-American food, and in the same way, Brits of all backgrounds, like those queuing for Jerk In Da Park, have embraced a new British palette.20 It is born from the Caribbean diaspora, from first, second and third generation individuals. British Caribbean food is a culture that is fed in abundance. It is developed in jars and containers, by people like Dionne, who draws from her Jamaican and Guyanese heritage to create iconic flavour combinations, such as her Mango Pepper Sauce, that customers specially request. Towards the end of our conversation Dionne and Prentis assure me that ‘anytime of day, morning or evening, food will always be here’. Together, they tirelessly sustain this culture, preparing food each day, before the sun rises. And it is challenged, splintered and remodelled by those pushing boundaries such as the Trinidadian eatery in Arsenal that Robinson speaks so fondly of. British Caribbean food is a culture that is fed, developed, sustained, challenged, splintered and remodelled. It therefore has a rhythm, with undulations, diversions, distractions and breaks. London dances to its rhythm, imitating the flicker of its kitchen flame. Turn up the heat, there’s plenty to go around.

‘That’s how we do it. Real ting.’ – Prentis, Jerk In Da Park. But when it comes to the food of a diaspora, what is the real ting?

~

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Dionne and Prentis from Jerk In Da Park for speaking with me about Caribbean food in London and for letting me into their sacred space: the kitchen. If you ever find yourself in London, you must head down to sample their food. They are open Monday – Friday, 8am – 2pm and their menu posted daily on Instagram (@official_jerkindapark) and Facebook (@Jerk in Da Park/ Jackson’s Catering). Thank you for sharing your stories, your history and your joy.

Also a special thank you to Roger Robinson, for being so open and willing to chat about Trinidadian culture, Black British culture and Caribbean food across the UK. Your work is beautiful and thought-provoking … a formidable voice of our time. Robinson’s latest publication, ‘Home Is Not A Place’ is available to purchase online.

Notes

1 Jerk In Da Park’s Instagram page, @official_jerkindapark, where they post daily menus and updates.

2 Bankside Open Spaces Trust, https://www.bost.org.uk/.

3 Samuel Selvon, The Lonely Londoners (Longmans, 1956); Poet and the Roots, Dread Beat an’ Blood, Produced by Linton Kwesi Johnson and Vivian Weathers (Gooseberry Sound Studios, 1978).

4 Roger Robinson, ‘Windrush’ in A Portable Paradise (Peepal Tree Press Limited, 2019).

5 Roger Robinson and Johny Pitts, Home Is Not A Place (William Collins, 2022).

6 Johny Pitts, ‘Odyssey of the overlooked: a journey around Black Britain’, The Guardian (September 11, 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/11/odyssey-of-the-overlooked-a-journey-around-black-britain [Accessed on September 26, 2022].

7 Riaz Phillips, Belly Full: Caribbean Food in the UK (Tezeta Press, 2017), p. 8.

8 Ibid, p. 11.

9 Ibid, p. 16.

10 Ibid, p. 19.

11 Ibid, p. 19.

12 Riaz Phillips, ‘Caribbean food and cultural spaces rebuilt parts of the UK that had been neglected | Windrush 70th Anniversary series’, Media Diversified (June 20, 2018), https://mediadiversified.org/2018/06/20/caribbean-food-and-cultural-spaces-rebuilt-parts-of-the-uk-that-had-been-neglected-windrush-70th-anniversary-series/ [Accessed on August 23, 2022].

13 Roger Robinson, ‘Windrush’ in A Portable Paradise (Peepal Tree Press Limited, 2019).

14 Rowan Moore, ‘London: the city that ate itself’, The Observer (June 28, 2015), London: the city that ate itself, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jun/28/london-the-city-that-ate-itself-rowan-moore [Accessed on July 27, 2022].

15 Jonathan Nunn, ‘London Eats Itself, London Plays Itself, London Feeds Itself’, Vittles (July, 27, 2022), https://vittles.substack.com/p/london-eats-itself-london-plays-itself [Accessed on July 27, 2022].

16 Ibid.

17 Nandina Hislop, ‘Tracing roots of the Chinese Jamaican diaspora’, Gal-dem (September 4, 2021), https://gal-dem.com/tracing-roots-of-the-chinese-jamaican-diaspora/ [Accessed on November 9, 2022].

18 Jonathan Nunn quoted in ‘The Diversity of Caribbean Cuisines’, written by Keshia Sakarah, Vittles (June 12, 2020), https://vittles.substack.com/p/vittles-214-the-diversity-of-caribbean?s=r [Accessed on November 10, 2022].

19 Ibid.

20 Ligaya Mishan, ‘Asian-American Cuisine’s Rise and Triumph’, The New York Times (November 10, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/10/t-magazine/asian-american-cuisine.html [Accessed on June 29, 2022].