RE-ENVISION: European Stuffed Pasta

By Thomas Martinez and the Appetite Team

RE-ENVISION is an ongoing series of crossroads research memos produced by our associates at Appetite. We trace the cultural genealogies of food from around the world to challenge commonly held beliefs about origin and authenticity.

Make dough. Prepare filling. Wrap dough around the filling. Cook. Serve.

This overly simplified recipe might immediately bring to mind a Chinese wonton, an Indian momo, or maybe even a Mexican tamale. The similarities between these tantalizing food items make it apparent that dumpling-style foods are ubiquitous across all cultures and gastronomic traditions; for Europeans, the most acclaimed of these variations is the Italian ravioli. As one of the most recognisable European dumplings, they are a good entryway into a crossroads reading of the world of stuffed pastas.

The origins of ravioli

Ravioli are small Italian dumplings made by encasing a filling of ground meat, cheese, vegetables and herbs between two thin layers of pasta. They are cooked by boiling, tossed in a sauce of varying compositions, and typically served with a light drizzle of oil. A single raviolo’s ingredients may vary from region to region in Italy. In the small village of Scapoli in Molise, Italy, ravioli is filled with boiled and chopped chard, roasted ground meat, sausage, eggs, ricotta, and young pecorino cheese1. Similarly, in Campania, Ravioli di ricotta di Pecora (sheep’s cheese ravioli) is the specialty.

The first recorded ravioli, described in a letter sent by the 14th-century merchant Francesco di Marco Datini, was filled with pork, eggs, cheese, parsley, and sugar2. Eurasian trade was already commonplace at the time of Datini’s correspondence, and the ingredients found in his description can still be found in the ravioli of today. For example, today’s ravioli filling typically includes ricotta, egg, spinach, nutmeg, and black pepper. These ingredients have all ancient and diverse histories and are believed to have originated in the Italian peninsula in 2000 BCE3, Southeast Asia and Indian Subcontinent before 7500 BCE4, Ancient Persia during the first century BCE5, the Banda Islands of Indonesia in 1500 BCE6, and India around 2000 BCE respectively7.

The sauces that accompany ravioli also host well-traveled ingredients. For instance, the tomato sauce that often blankets the stuffed Italian staple wouldn’t have been possible without the transfer of the tomato from the New World to the Old World during the Columbian Exchange in 15th century CE9. The ingredients that constitute the ravioli’s filling and its sauce denote the dishes’ undeniable intercultural makeup.

The disputed origins of pasta dough

However, there is contention around the origins of one fundamental ingredient of Italian stuffed pasta: the dough. The outer layer of the dumpling— the pasta dough holding together all ingredients— is itself an item of significant intrigue. This essential component of ravioli and all other pasta dishes is conventionally made from semolina flour, which is milled from durum wheat9. Durum wheat was initially found in the Levant and the Ethiopian Highlands around 7000 BCE and is believed to be one of the first domesticated crops10 11. Yet, despite knowing the roots of a basic element of pasta, historians and pasta lovers still debate the origins of the Italian delicacy.

There are several theories that pasta connoisseurs staunchly abide by, the first of which is that pasta dough is an invention of Italian origin. They cite their claims with the existence of proto lasagna-type pasta dating back to 400 BCE12. The excavation of an Etruscan tomb found ancient pasta-making tools, signifying that pasta was enjoyed by the Etruscans and the Romans alike. However, findings indicate that these early pastas were more likely to have been baked rather than boiled like conventional variations of the dough13.

Alternatively, reputable scholars, such as prominent food writer Charles Perry and food historians Alan Davidson and Professor Barbara Santich, link the origins of pasta dough to Central Asia14 15 16. They note that Arabs brought itriyah, dried dough of flour and water cut into strips, to Italy through the conquest of Sicily and Southern Italy during the 9th century CE17. Unlike the Etruscan pasta, itriyah required boiling to be made palatable, indicating that itriyah’s cooking process is akin to that of modern pasta dough18 19. The Middle Eastern analogue is referenced in the Talmud as having been consumed in Jerusalem and by Arab traders along the Silk Road during the 5th century. Moreover, the word itriyah is believed to be derived from the Ancient Greek phrase itrion, which refers to a ceremonial flatbread20. Today, Sicilians use the term tria to refer to various pastas, showing there is, at least, some connection between the early Arab pasta and its modern counterpart21 22.

The question of Marco Polo and China

Another theory concerning the origins of pasta dough strings the development of the Italian staple to Chinese noodles. This popular myth purports that pasta was brought to Italy by the Venician merchant Marco Polo in 1292 CE23. However, the foremost problem with this theory is that, in The Travels of Marco Polo, Polo makes note of lagana, a lasagna-esque dish, which would suggest that pasta existed before his travels24. We also do not know whether Marco Polo really did venture into China and serve in the court Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan25.

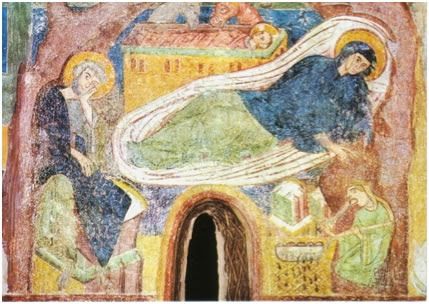

It should be noted that “dumpling” style foods did exist in Italy long before Polo’s ostensible travels. The first century CE Roman Cookery text, the Apicius, describes a dumpling style recipe26. There is also a fresco that dates to the first decade of the 13th century known as mangiatrice di canederli (dumpling eater) in the chapel of Castel d’Appiano in Northern Italy27. However, these proto-stuffed pastas were more akin to a gnocchi-like dish. They were boiled balls of dough with mixed ingredients such as roasted pheasant, milk, onion, parsley, salt, and pepper28.

The first documented evidence of Italian dumplings in 1295 may have less to do with Polo’s travels and more to do with Venice becoming a dominant port for Mediterranean and Asiatic commerce29. Foodstuffs were exchanged throughout the cities of Trebizond (Trabzon, Turkey), Constantinople (Istanbul), Asiatic Tripoli (Lebanon), Antioch (Turkey), Beirut (Lebanon), and Alexandria (Egypt), influencing the culinary composition of Italy and the rest of Europe30. 14th and 15th century trade throughout the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Mediterranean likely also brought dishes like Central Asian manti, Indian momos , and Chinese wontons into Italy, leading to the stuffed pasta-dumplings (ravioli) of Renaissance Italy31.

Ravioli would even make its way into the kitchens of King Richard II of England32. This is evidenced by his chef’s cookbooks which contained recipes for ravioli as “rauioles.” It is also believed that the inception of Italian stuffed pasta lead to the development of food items like Polish pierogi33. Although Marco Polo should not be credited for the rise of pasta in Italy, it is inarguable that after his journeys, stuffed pasta began their final stages of development.

Central Asian and Mongol influence in other European dumplings

While nothing should dampen the Italian pride revolving around their stuffed pasta such as tortellini and ravioli, it is nearly undeniable that Central Asian and Mongol influence is present in other European dumplings. For instance, a Polish kreplach is a Jewish dumpling filled with meat and mashed potatoes, made by boiling the pocket of dough in soup. Although the cooking techniques allude to a comparable background with the ravioli, this dish’s origins more likely lie with Mongols and the Turkic manti 34 35. (The manti is a dumpling consisting of a ground or chopped meat, wrapped in a pasta or wonton like dough, and either boiled or steamed36.)

During the 13th century CE, interactions between the Mongols and the Armenian people introduced Chinese dumplings like bao and mantou to the West. From that point on, Turkic and Mongol migration along the Silk Road brought the dumpling into Anatolia, eventually making the manti known to the Ottoman Empire37. Time and cultural exchange led to its manifestation in kreplach and related dumpling dishes like Bosnian Klepe.

Similarly, the Russian pel’meni is also believed to have Mongol influences38. It is credited to the people of Siberia and the Ural Mountains, yet there are theories that propose the Mongols carried knowledge of dumplings, like the Chinese jiaozi, into these regions and eventually to Eastern Europe39. Ultimately, these analogues support the theory that European dumplings have taken many forms due to a myriad of cultural influences.

Ravioli, as the most recognisable of European dumplings, is a good entryway into the world of stuffed pastas. The source of its invention, like so many of its counterparts, is interlaced and muddled, showing that stuffed pastas are undoubtedly influenced by interactions throughout Eurasia. Regardless of which dumpling is the antecedent, stuffed pastas are an ever-evolving and continually popular dish, bursting with the intersecting histories of cultures around the globe.

For further reading, check out our previous research memo, RE-ENVISION: Dumplings.

Notes

1 “Tortelli and Ravioli,” The Pasta Project, March 25, 2019, https://www.the-pasta-project.com/tortelli-and-ravioli/.

2 Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

3 Paul Kindstedt Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization, (Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2012).

4 Don R. Brothwell, Patricia Brothwell, Food in Antiquity: A Survey of the Diet of Early Peoples (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press: 1998).

5 Arnau Ribera, Rob van Treuren, Chris Kik, et al, “On the origin and dispersal of cultivated spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.)”, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 68, 1023–1032 (2021).

6 James Hancock, “The Early History of Clove, Nutmeg and Mace”, World History Encyclopedia, 13 October 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1849/the-early-history-of-clove-nutmeg–mace/

7 James Hancock, “Pepper”, World History Encyclopedia, 2 September 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/Pepper/

8 Tijana Radeska, “Before the Columbian Exchange There Were No Tomatoes in Italy and No Paprika in Hungary,” The Vintage News, September 16, 2019, https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/08/30/priority-columbian-exchange-no-tomatoes-italy-no-paprika-hungary/.

9 R. A. T. Nilusha, J. M. J. K Jayasinghe, O. D. A. N. Perera, et al, “Development of Pasta Products with Nonconventional Ingredients and Their Effect on Selected Quality Characteristics: A Brief Overview”, International Journal of Food Science, vol. 2019 (2019).

10 Stephanie Stiavetti, Garrett McCord, and Matt Armendariz, Melt: the Art of Macaroni and Cheese (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013).

11 Corby Kummer, “Pasta,” The Atlantic (Atlantic Media Company, July 1, 1986), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1986/07/pasta/306226/.

12 13 14 “History Of Ravioli: THE NIBBLE Blog – Adventures In The World Of Fine Food,” History Of Ravioli | THE NIBBLE Blog – Adventures In The World Of Fine Food, October 2007, https://www.thenibble.com/reviews/main/pastas/history-of-pasta.asp.

15 “Who Invented the Noodle, Italy or China?,” Food, July 28, 2016, https://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2016/07/29/who-invented-noodle-italy-or-china.

16 Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

17 Corby Kummer, “Pasta,” The Atlantic (Atlantic Media Company, July 1, 1986), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1986/07/pasta/306226/.

18 Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, A History of Food (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

19 20 Corby Kummer, “Pasta,” The Atlantic (Atlantic Media Company, July 1, 1986), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1986/07/pasta/306226/.

21 “Pasta Is Not Originally from Italy,” Today I Found Out, November 28, 2012, https://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2011/06/pasta-is-not-originally-from-italy/.

22 Kantha Shelke, Pasta and Noodles – a Global History, (Reaktion Books, 2016).

23 “Pasta Is Not Originally from Italy,” Today I Found Out, November 28, 2012, https://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2011/06/pasta-is-not-originally-from-italy/.

24 Tori Avey, “Uncover The History of Pasta,” PBS (Public Broadcasting Service, July 26, 2012), https://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/uncover-the-history-of-pasta/.

25 Jennie Cohen, “Marco Polo Went to China After All, Study Suggests,” History.com (A&E Television Networks, April 17, 2012), https://www.history.com/news/marco-polo-went-to-china-after-all-study-suggests.

26 Stephanie Butler, “Delightful, Delicious Dumplings,” History.com (A&E Television Networks, March 28, 2014), https://www.history.com/news/delightful-delicious-dumplings.

27 Barbara Gallani, Dumplings: a Global History (London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2015).

28 Fr@, “Knödel (Canederli) Con Lo Speck in Brodo,” Sciroppo di mirtilli e piccoli equilibri, January 1, 1970.

29 30 31 Radim Kolarsky, “The Dumpling Page ,” The Dumpling Page, accessed January 23, 2020, http://www.kolarsky.com/family/cookbook/dumplings.htm.

32 Nationality Today, “National Ravioli Day – March 20, 2020,” National Ravioli Day – March 20, 2020, 2017, https://nationaltoday.com/national-ravioli-day/)

33 “Facts & History About Pierogi,” Enjoy Organic Pierogi From Polska Foods, May 2, 2014, http://www.polskafoods.com/polish-food/facts-history-about-pierogi)

34 Schoolchanger, “Kreplach: A Look Beneath the Dough,” foodhistoryreligion, September 3, 2018, https://foodhistoryreligion.wordpress.com/2015/10/08/kreplach-a-look-beneath-the-dough/.

35 Mark McWilliams, Wrapped & Stuffed Foods: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012 (Totnes, Devon, England: Prospect Books, 2013).

36 Tami Weiser, “The Delectable Dumpling Diaspora,” Moment Magazine – The Next 5,000 Years of Conversation Begin Here, August 14, 2019, https://momentmag.com/delectable-dumpling-diaspora/.

37 Aylin O Tan, ”Manti and Mantou: Dumplings Across the Silk Road from Central Asia to Turkey.” in Wrapped & Stuffed Foods: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012, ed. Mark McWilliam, (Totnes, Devon, England: Prospect Books, 2013), 144-165.

38 Barbara Gallani, Dumplings: a Global History (London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2015).

39 “Dumplings from Around the World”, BBC Bitesize, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/ztgxm39

Annotated References

Gallani, Barbara. Dumplings: a Global History. London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2015.

In this book, Barbara Gallani, director of food safety and science at the UK Food and Drink Federation, provides an in-depth history of the development of dumplings around the globe. Specifically, she connects dumpling style cuisine across the AfroEurasian supercontinent, showing how techniques and ingredients are not a product of a single culture.

“History Of Ravioli: THE NIBBLE Blog – Adventures In The World Of Fine Food.” History Of Ravioli | THE NIBBLE Blog – Adventures In The World Of Fine Food, October 2007. https://www.thenibble.com/reviews/main/pastas/history-of-pasta.asp.

This article discusses the development of Ravioli from antiquity into the modern-day. It introduces the competing theories surrounding its origins as some scholars believe that European dumplings are a product of Asian influence while others support the dish is solely product Italy. Interestingly, this article presents the theory that the dumplings rise in Europe is a product of Marco Polo’s expedition to China.

Julia. “Pasta Is Not Originally from Italy.” Today I Found Out, November 28, 2012. https://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2011/06/pasta-is-not-originally-from-italy/.

This blog addresses common misconceptions about the evolution of pasta. In addition to swiftly discrediting the theory that pasta’s conception is a result of Marco Polo’s voyage, it discusses the belief that pasta is a result of trade and conquest by the Arabs. Furthermore, it also tells of pasta’s presence in early Jewish community by citing the Talmud, indicating a possible connection to Italian dumpling as the Jewish people entered Europe.

Kummer, Corby. “Pasta.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, July 1, 1986. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1986/07/pasta/306226/.

This article provides a wealth of information on the origins of pasta. Its content elaborates on theories explored in other reports, providing information as a means of cross-reference and expansion. It also provides significant insight on the history and use of itriyah in the Middle East.

Weiser, Tami, and Tami Weiser. “The Delectable Dumpling Diaspora.” Moment Magazine – The Next 5,000 Years of Conversation Begin Here, August 14, 2019. https://momentmag.com/delectable-dumpling-diaspora/.

This article tells of myriad connections between European dumplings and their relationship to the Jewish diaspora. Specifically, it discusses the likelihood of the manti having influenced the kreplach and other dumplings popular in Jewish communities. This creates an additional reference for the dumplings development through the Middle East.

“Who Invented the Noodle, Italy or China?” Food, July 28, 2016. https://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2016/07/29/who-invented-noodle-italy-or-china.

This report provides the perspectives of specific academics about the development of the pasta. By connecting the research of various scholars, this piece drafts a clear image of the origins of pasta. It shows that although Chinese noodles and dumplings might have impacted the development of European pasta, these influences should not be credited for the creation of items such as pasta and ravioli.

McWilliams, Mark. Wrapped & Stuffed Foods: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012. Totnes, Devon, England: Prospect Books, 2013.