RE-ENVISION: Pickles (Sweet & Sour Power: Pickle Politics)

By Frankie Jenner

RE-ENVISION is an ongoing series of crossroads research memos produced by our associates at Appetite. We trace the cultural genealogies of food from around the world to challenge commonly held beliefs about origin and authenticity.

Food is one of the most powerful ways we can use to begin making sense of the world around us. Culinary history and historiography enable us to understand not only the many dishes we love, but also the story of the peoples, places and identities involved in their making. A study of food is ultimately a study of people.

Food’s inextricable relationship to history and politics

In a recent interview for Southeast Asia Globe, Appetite’s very own Ivan Brehm demonstrates the role of food in the current Russo-Ukraine war. Using dumplings as an example, he argues the difficulty of ascertain rights of ownership and authenticity; dumplings came to both countries through interactions with Turkic people crossing the Central Asian plateau. Russians have pelmeni, Ukrainians have varenyky, Koreans have mandu, Poland has pierogi, manti gave rise to Chinese mantou in China and Azerbaijan’s dyushbara.

Dumplings are a ubiquitous feature atop the disparate dinner tables of these countries. Pelmeni is believed to have arrived in Russia with the nomadic Mongols who migrated through Siberia and the Urals, and further into Eastern Europe in the 14th century. The delicate pleats of the pelmeni dumpling therefore come to symbolise more than just careful curation – they speak to the historical ties between Europe and Asia.1

Through the lens of pickling and fermentation, we can look also to borsch; a dish whose origins are heavily contested by Russians and Ukrainians, with both battling to secure its ownership.

Borsch, Source: @Olia_Hercules on Twitter.

The debate bubbled over into Twitter in 2014 when Russia’s official account tweeted: “A timeless classic, #Borsch is one of Russia’s most famous & beloved #dishes & a symbol of traditional cuisine.”2 This was broadcast in the midst of the Russian occupation of Crimea and the escalating territorial conflict in Eastern Ukraine that had been raging since 2014. Ukrainian Twitter united in their response: “As if stealing Crimea wasn’t enough, you had to go and steal borsch from Ukraine as well.”3 While humorous to observe how a bowl of soup could trigger such fury back and forth over keyboards and illuminated screens, this Twitter spew shed light on the much larger trend of Russia’s historical oppression of Ukraine. Its claim to borsch, just another of its attempts to assert political dominance over the nation.

A tweet from Russia’s official Twitter account in 2019, Source: @Russia on Twitter.

The soup is believed to have originated from what is now Ukraine, sometime before the 9th century. In its conception, the main ingredient was hogweed: a tall, cow parsley-like plant. It was chopped up, placed in water to ferment and then its pickled stems would be mixed with a broth, eggs and cream to make a rich soup. The more widely recognised version of borsch that we see today contains beetroot, which imparts its iconic and striking magenta red colouring. This addition of beetroot was introduced towards the end of the 17th century, by those living in Eastern Ukraine. 4

Towards the end of the 19th century, imperial expansion and transport developments took the dish across the depths of the Russian empire, into Persia, Westwards to French chefs and catapulted into the US as Ashkenazi Jews fled from persecution in Eastern Europe during the 20th century.5 Pickling still remains at the forefront of today’s various iterations of the dish, which often feature pickled beetroots and dill pickle juice.

Brehm says that “to talk of dumplings as [both] a trademark of Russian and Ukrainian history [shows] that they are not isolated at all” and any attempt to separate them, errs on its artificiality… the same can be said for borsch.6 The soup’s story illustrates how food plays such a large role in shaping cultural and historical discourse. This is a concept that also serves as an anchor point for ‘Pickle Politics’, a research cycle by the collective Slavs and Tatars.

Slavs and Tatars: Reconsidering the histories of Eurasia

Installation view of ‘Pickle Tits’ at the Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, 2018. Source: Thorsten Arendt.

Slavs and Tatars are an art collective founded in 2006 by the Polish-Iranian duo, Payam Sharifi and Kasia Korczak. It was initially established as a reading group for out-of-print works and texts that were unavailable in English. But over the years, it has evolved and many other artists and researchers from around the globe have joined.7 For Slavs and Tatars, Eurasia is their geographical anchor. Their approach seeks to reconsider the histories of the Eurasian continent, which has been largely misunderstood and forgotten. As such, they offer a critical reflection of the Western gaze on the region. Littered with satirical humour and childish wit, their work introduces the largely arcane subject matter to an international audience in the hope to ‘resuscitate’ the region and explore knowledge exchanged between Slavs, Caucasians and Asians.8 9 10

The Eurasian Steppe. Source: Grass Roots: Pathways to Eurasian Cultures at the Miami University Art Exhibition, https://muamgrassroutes.wordpress.com/2012/06/05/a-map-of-the-steppes/ (Accessed on March 21, 2022).

The collective defines Eurasia as the geographical region between the former Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China; it runs through what is now modern-day Mongolia, Kazakhstan, the European part of Russia and into Ukraine. The Eurasian Steppe forms a large part of the region, it’s a vast plain of grassland, Savannah and shrub-lands that extends eight-thousand kilometres from East to West. The Steppe region was occupied by several historic empires of pastoral nomads, such the Xiongnu, Göktürks, Khazaks and the Mongols. Historically, it has been one of the most important routes for commerce as it lay the foundations for passages such as the Silk Road which was a complex network of trade routes that connected the Eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia and through to China.

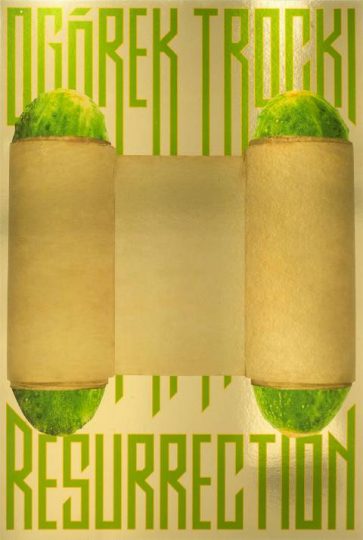

Slavs and Tatars, Ogórek Trocki, 2016, offset print on gold paper.

As part of their work, Slavs and Tatars use a variety of different mediums such as sculpture, installation, posters, exhibitions, performance-lectures and printed publications to explore the different traditions, practices and histories of Eurasia. ‘Pickle Politics’ is one of their research cycles that uses fermentation to consider the transformative conditions of politics and culture.11 In their inaugural exhibition at SUGAR in Toronto, the collective plastered posters of Ogórek Trocki (2016) around the space, covering benches and framing videos. It presents an image of two cucumbers wrapped in a Torah scroll.

This is the Trakai Cucumber that was cultivated by the Crimean Karaites, a sect of Turkic-speaking anti-rabbinical Jews. This variety of cucumber originated from a city of the same name in Lithuania and was subsequently brought to the Baltics and Poland by the Crimean Karaites when they emigrated during the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 14th century. It was famed for its high sugar content and therefore considered ideal for pickling. The cucumbers were submerged in barrels full of brine, nailed shut and thrown into lakes over the winter months. In the spring, the Karaites would cut through the icy surface of the lake and extract the barrels filled with perfectly pickled cucumbers. But during World War Two, the Trakai seeds stopped sprouting and the famous cucumber was lost after 400 years of cultivation. 12

The Journey of the Trakai Cucumber from Lithuania to Poland. Source: Frankie Jenner.

Pickling as an anti-binary metaphor

But for Slavs and Tatars, tracing the Eurasian roots of pickling is not just an attempt to resuscitate these forgotten or endangered histories; pickling also comes to serve as a larger metaphor. Pickling becomes an anti-binary metaphor. This means that what initially appears to be opposing elements (binaries), actually have the potential to co-exist. Pickling therefore presents a direct challenge to the Western Enlightenment’s legacy of binary thought. Fermentation is a process of controlled decay; achieved via its counterintuitive antithesis.13 It involves not just life, but also death; bacteria decay, rot and decompose over time as they self-digest.14 In a strange way, death actually creates new life. Anna Kovler identified that when we look at both history and pickles, we can locate a series of binaries: food and bacteria, Islam and Christianity, and atheism and religion that actually develop alongside one another. 15

Within pickling’s fermentation process, we can observe similar relationships within the different types of ‘souring’. There is the bittering, or rotting that we previously explored in relation to assimilation. But there is also the process of transmogrification. This is where multiple substances are activated and alter into another: they become something else.16 Through their coexistence, new life develops. This transformation is dramatic and can be witnessed: through sight, taste and smell. The various colours and textures within the vessel begin to alter, which produce an array of different tastes, such as umami and sweetness. The fermenting body consumes bacteria from its immediate environment and integrates it into its very form. Fermentation therefore displays a paradox of both preservation and transformation.

When we delve deeper into the story of the Trakai cucumber, we can identify a series of binaries that begin to display characteristics of syncretism. Disparate cultures, religions, schools of thought, rituals and traditions begin to amalgamate and enrich one another. The Karaites had a remarkably syncretic approach to faith. Having lived amongst majority Muslim populations for over a millenium, many of their rituals and traditions speak a lot to that of Islam. Like many Muslims, they have basins outside their kenessas (synagogues) to wash themselves, shoes must be taken off before entering places of prayer and followers often practise full prostration (bowing with arms outstretched) during prayers. These supposed binaries, Islam and Judaism, developed together, borrowing and learning from one another. This is the cultural ferment. It is lively and it is collaborative.

The story of pickles is one that illuminates how disparate communities and cooking styles come together. As people move across geographical borders, they bring with them rituals and practices when they are not able to bring the ingredients. Food becomes an agent for cultural preservation. Slavs and Tatars illustrate this through a bazaar approach to contemporary art. Instead of focusing on a particular sculpture or object to convey meaning, they adopt more of a big tent outlook. If the viewer is more attuned to literary or academic work, they can access their publications; if they are more engaged in the performative aspect, they can watch the lectures; and if they are more competent with visual elements they can use works such as Ogórek Trocki as an entry point. Having multiple different access points is a deliberate effort to make the narratives as accessible as possible. By tracing the story of pickles through the work of Slavs and Tatars, we are able to not only uncover forgotten or misunderstood food histories, but also trace the syncretism of various communities: the cultural ferment. The techniques and traditions of pickling and fermenting contain the stories of migration, assimilation and shifting political geographies.

Slavs and Tatars, Pickle Tits, 2018–21, installation view, Balade, 2021. Source: the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York City, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin, Raster Gallery, Warsaw, and The Third Line, Dubai.

Fermentation and the souring of motherhood

But this co-existence is not always progressive. In the same way that fermentation is not always successful. In ‘Pickle Tits’, an installation erected in Charlottenburg, Berlin in 2021, two advertising columns question the socio-political role of mothers within society. Pickles come to take on a new form; swollen breasts from which mother’s milk drips to form a poem: ‘The Soured Rule, No Mother’s Best, Curd Milk Oozing, From its Breast’. This is translated into five languages – German, Hebrew, Polish, Russian and Turkish – as a reflection of the multicultural makeup of the neighbourhood as well as speaking to the similar maternal longings amongst these ethnic groups.17

Fermentation is now accessible through a feminist framework. Lauren Fournier is a curator, writer, artist and researcher who established the programme Fermenting Feminism in 2017. The project explores how feminism can be approached through the metaphorical and material practice of fermentation.18 It brings together the work of artists who approach these themes through intersectional and trans-inclusive frameworks.

Fournier describes fermentation as a ‘natural process of enrichment in which the ‘mother’ procreates, regenerates, feeds, cares and self-replicates or updates herself.’19 This idea of motherhood within fermentation is interesting. Often, a fermentation starter is referred to as the ‘mother’. This is the foundational mixture needed to assist the beginning of the fermentation process. Pre-ferments are particularly crucial when making foods such as sourdough, kombucha, sauerkraut and cheese. The ‘mother’ therefore adopts a role of nourishment and care.

So when we look again at Pickle Tits through the framework of Fournier’s Fermenting Feminism, the nourishment that is stereotypically associated with a matriarchal state has now soured, and turned into kefir. The mother can no longer enrich. One can’t help but think of the recent escalation of conflict in Ukraine in relation to the souring of motherhood. A poignant article published on Time by Simmone Shah reveals that while some 3 million Ukrainians have fled the country since the Russian invasion began, almost all of whom are women and children, there is also a contingent of women returning East to their families. Grandmothers tending to the babies of Ukrainian soldiers, mothers attempting to rescue their children and daughters hoping to wait out the war with their parents.20 While it is very much a contemporary conflict, it has highlighted entrenched gender stereotypes surrounding war. Whilst there is no official forced conscription, the majority of men aged 18 through to 60 are not allowed to leave the country and are widely shamed if they do not volunteer to defend their homeland. Likewise, women are very much encouraged by the state to prioritise the needs of the family, tending to their children and ensuring they are out of harm’s way.

Mother holds newborn baby in the bomb shelter of a maternity hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine. Source: Getty Images.

Since Russia’s invasion, photos have been published of women giving birth in metro stations and newborns being hurried to makeshift bomb shelters as critical health facilities have been destroyed, like the maternity hospital that was bombed in Maripoul in early March. It is estimated that approximately 80,000 women will give birth in Ukraine in the next three months.21 Many of these women will have no access to maternal health care. Child birth all of a sudden has become a life-threatening experience as opposed to a life-changing and enriching one. These photographs and stories illuminate how motherhood has rapidly become a treacherous ridge that women are being forced to traverse, alone.

Motherhood. The stir of incipient life. A novel, unbegun. But these children are thrust into a world of trepidation, agitation. These children are collages of the destruction that surrounds them. The mother’s duty, to protect, care and nourish … a duty she can no longer fulfil. How powerful it is to be able to bring life into this world. How devastating it is that this life be delivered precariously, unsafely. A dichotomy of fulfilment and emptiness prevails. The mother is called to nurture, despite her exhaustion, confusion and pain. Once a vessel for life, starts to rot, becoming a receptacle for grief. The game of motherhood is rigged. A novel whose foundations have already been obliterated. Four years after the erection of Pickle Tits, its bitter reflection has never been more poignant to our current times.

The Cultural Ferment

Fermentation offers us a lens through which we identify these powerful binaries: life and death, decay and cultivation. In this way, bacterial cultures are akin to societal cultures. Whilst death will always be prominent and visible, life will also flourish. Against the horrific backdrop of war, there has also been an incredible outpour of support for all those affected; whether that be bake sales, auctions, the #CookForUkraine campaign, provision of legal aid, communities united in prayer, people opening up their home to refugees and foreign fighters volunteering on the ground.

Through these parallel developments, we can chart how culture develops: through an exchange, a meeting, a transfer. Whilst we must not lose sight of the suffering and extreme loss, it is exciting to think about the future. How will our cultures be enriched by the arrival of new life? As Ukrainian refugees settle in countries across the globe, as their stories are uttered, as their meals are shared, as their language is imparted and as their traditions are enacted, what will we take away? We are witnessing a convergence at the crossroads, a moment that will, if we allow it, help us to conceive beyond our limitations and ways of seeing. And we will marvel at this healing because each translation will offer transformation.

Thirsty for more? Check out the companion article, Sweet and Sour Power: What’s the Big Dill.

Notes

1 Olia Hercules, ‘Let Me Count the Ways of Making Borscht’, The New Yorker, December 7, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-gastronomy/let-me-count-the-ways-of-making-borscht (Accessed on March 15, 2022).

2 Russia (@Russia), Twitter, May 30, 2019, https://twitter.com/d1ml1v/status/1134045739611578369 (Accessed on March 21, 2022).

3 Andrew Evans, “Who really owns borsch?”, BBC, October 15, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20191014-who-really-owns-borsch (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

4 Ibid.

5 Alexander Lee, “From Russia with Borscht”, History Today, 68, no. 8 (2018), https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/russia-borscht (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

6 Amanda Oon, “Singapore’s Ukrainian-Russian restaurateurs build bridges with dumplings”, Southeast Asia Globe, March 23, 2022, https://southeastasiaglobe.com/singapores-ukrainian-russian-restaurateurs-build-bridges-with-dumplings/. (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

7 Deena Chalabi, “Interview with Slavs and Tatars”, Stages – Issue 1, https://www.biennial.com/journal/issue-1/interview-with-slavs-and-tatars- (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

8 Agnes Monod-Gayraud, “Slavs and Tatars”, Culture.pl, Last updated May 2021, https://culture.pl/en/artist/slavs-and-tatars (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

9 Gabriela Matuszyk, “A matter of (sour) taste”, Eye Magazine, July 30, 2020, https://www.eyemagazine.com/blog/post/a-matter-of-sour-taste, (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

10 Andres Kreuger, “Beyond Nonsense: What Slavs and Tatars Make”, Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 31 (2012), pp. 110, https://doi.org/10.1086/668927.

11 Slavs and Tatars “Pickle Politics” at SUGAR, Toronto”, Mousse Magazine, Jan 27, 2020, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/slavs-and-tatars-pickle-politics-at-sugar-toronto-2019-2020/ (Accessed on February 23, 2022).

12 “Royal Fields or Karaite Fields”, Trakai Visit, https://www.trakai-visit.lt/en/royal-fields-or-karaite-fields-2/ (Accessed on February 23, 2022).

13 “Slavs and Tatars”, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, https://www.k-t-z.com/artists/37-slavs-and-tatars/works/4390-slavs-and-tatars-salty-sermon-2020/ (Accessed on February 23, 2022).

14 Elena Beregow, “Cooked or Fermented? The Thermal Logic of Social Transformation”, Culture Machine, Vol 17. Thermal Objects (2018), https://culturemachine.net/vol-17-thermal-objects/cooked-or-fermented/ (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

15 Anna Kovler, “Critics Picks: Slavs and Tatars”, Art Forum, https://www.artforum.com/picks/slavs-and-tatars-81513 (Accessed on February 15, 2022).

16 Katarzyna Czeczot, “The Enlightenment Is the Booty: Slavs and Tatars”, Mousse Magazine, November 11, 2016, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/the-enlightenment-is-the-booty-slavs-and-tatars/ (Accessed on June 14, 2022).

17 “Pickle Tits”, Balade Berlin, https://balade-berlin.com/2021/station/5-litfassaeule/?lang=en (Accessed on February 26, 2022).

18 Lauren Fournier, Fermenting Feminism, (Berlin and Copenhagen: Laboratory for Aesthetics & Ecology, 2017), p. 3.

19 Ibid.

20 Simmone Shah, “‘I Have No Other Choice.’ The Mothers Returning to Ukraine to Rescue Their Children”, Time, March 16, 2022, https://time.com/6157816/ukraine-mothers-children-war/ (Accessed on March 21, 2022).

21 “Ukraine: Conflict compounds the vulnerabilities of women and girls as humanitarian needs spiral”, United Nations Population Fund, https://www.unfpa.org/ukraine-war (Accessed on March 12, 2022).