RE-ENVISION: How to Eat with Hands

By Jackson Kao, with the Appetite Research Team

Entry; July 9th.

Neha Tiffin stall at Tekka Center. Rava masala dosai. Pick gently at first. Burn your fingers lightly against the steaming spiced potatoes and the thin lacy semolina that encapsulates it like a cocoon. When putting the stuff into your mouth avoid making eye contact with the drink vendors who will be over in a flash, miming the knocking-back of a lassi or ginger tea, eyebrows raised with intent. Unless of course you want that and then by all means look on and even raise your dahl encrusted fingers and try not to spit when you shout.

‘Rava masala dosai’ implies a few things. Dosai are a savory pancake made from fermented lentils, eaten commonly for breakfast or lunch, or anytime as a quick bite. The pan is flicked with ghee, and the batter is spread thin, prodded and flipped. The finished dosai are folded and served with two or three chutneys and sambars, made usually from cashew, mint or tomato. Hot dahl is provided in a small styrofoam cup to moisten the dough. For masala dosai, a mixture of spiced potatoes with black mustard seeds and curry leaves is spread on the face of the dosai before it is folded. A rava dosai uses semolina flour in the batter instead of the traditional fermented lentils and the bread is punctured and typically crispier. Enjoying a dosai implies something else too, something truly unfamiliar to me amidst the new spices and textures: the act of eating without a fork and spoon, without anything but my hand. Dosai, in all their lovely iterations, become somewhat of a gateway to my interest in forsaking utensils, discovering how not only breads but entire meals could be enjoyed and understood when approached by the grace of the fingers; that my hands were tools in ways I hadn’t considered.

I was raised in the United States where food is consumed through intermediaries known as utensils or cutlery. Composed of metal and plastic and even porcelain or bamboo, they vary in shape and size but follow general functional forms. In my own years of experience, meals in American contexts are typically eaten with a knife and fork and sometimes an assortment of knives, forks, and spoons––chopsticks, occasionally. The act of eating by hand is associated with childhood barbarism, generally perceived as a habit to be stamped out well before adolescence. Though I understood that food could be eaten with hands and that in some parts of the world this was done, I had a knife and fork in my hand from a young age, and knew the drill of pinning down food with the fork and sawing away with the knife. It was never demonstrated to me that my hands could function any other way when eating food properly.

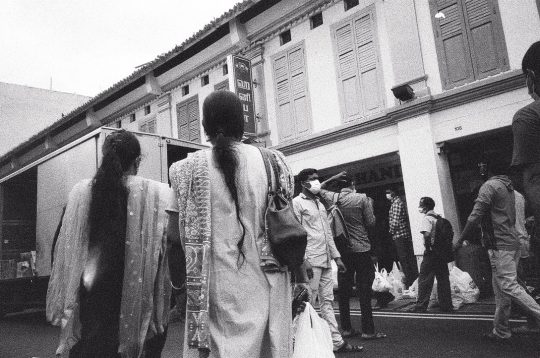

I arrived in Singapore on a wet morning and wandered to Little India on the insistence of my cab driver. The air was awash in billows of frankincense and rose and trucks clattered down the narrow roads dodging people ducking into tea shops and buying vegetables in the street. A few days later I moved into a hotel just blocks beside Tekka, Little India’s biggest hawker centre and wet market.

The ubiquitous custom of eating with hands throughout the neighbourhood drew my rapt attention, though I would thankfully accept the plastic utensils sent my way. Local diners never received the sympathetic roll-up and I began to gaze at that distance between us. It appeared that, seeing me, my darting eyes, hearing the hesitation in my accented voice, the measure of my total outsiderness was summed up tidily and I was provided cutlery before my mind could form the request. I sat surrounded by orchestras of fingers brushing their meals away, picking at my own dosai with a plastic fork and spoon, feeling in a corner of my mind that something was amiss.

In bigger shophouse restaurants, people tackled huge meals of rice and curried mutton spread across banana leaves, elbow cocked out, fingertips playing and raking little vegetables and bits of white rice into bite-sized bouquets. People dined alone, plucking rapidly, and in groups chatting energetically with smiling eyes. White plastic utensils might never have existed. The mercifully cool early mornings offered some clarity to my observations; before noon, the sun rushed me elsewhere.

One might argue that American classics like ballpark hotdogs and buttered corn-on-the-cob are eaten with the hands. Isn’t finger-food still a thing? Beyond holding the food, however, the fingers are not engaged when eating like this. They shy bashfully away from the wet and saucy bits; it’s a sort of giddy, brief departure from the norm. In Singapore, the fingers play a real role.

My initiation was bread. But it was not that simple. For varying religious, sanitary reasons, only the right hand touches food; the left hand rests in the lap or sprawls on the table. Despite this practical knowledge, my immediate, perpetual urge was to savagely rip my starches apart with both hands. I quietly scolded myself, straining for the good examples around me.

With a firm but relaxed hand, the middle and ring fingers pin down the bread while the thumb and forefinger rip smaller bites away. The bread is steaming but the fingers do not wait. Morsels reach their destination in a plucking manner, often eaten quickly but never carelessly. There are many sinks in the centres, busy with diners washing shades of red and yellow from their fingers and lips.

Meals built around rice were more daunting. I watched them arrive on the banana leaves with more than a dozen nameless accompaniments, an armada of curries, sambars, dhals, and crimson pickles.

When you’re a beginner at anything I suppose that to strive for grace would be missing the point. I began by giving my hands a good scrub in a nearby sink, by disregarding the paper-towel roll-up placed at the table’s edge. In an instant, a rice meal lay before me, sprawling across that lush banana leaf. A heaping of white rice centerstage threw off clouds of steam and stung my uncertain fingers; but what nipped at my fingers did not necessarily burn my lips… and everything balanced when mixed together with the cool of the sambars.

Following the lead of the more tenured diners, I in turn raked together little combinations of rice and dhal, formed my fingers together into a curved shovel, leaned way over, and tried vigorously to get every intended grain from the leaf to my mouth. The fingers sprang from my palm, shaking, dropping grains of rice, gathering them again. Their nerves became friendly with the texture and weight and temperature of each small dish before me. I learned from them what proportion of blisteringly salty pickled mango, cashew sambar, and rice struck my palate with particular delight and formed them as such. After a time, I looked up again. The leaf’s emerald face shown in its full, save for streaks of pastel sambar and a smattering of rice. Nearby, moustached uncles cooled their own spiced tea by pouring it between two silver cups. They sipped delicately.

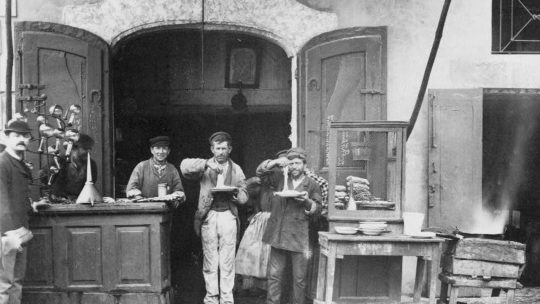

Singapore is a truly intense blend of regional populations for its limited geography. Local approaches to cooking and eating therefore include widespread usage of tools with which daily meals are achieved. In a New Yorker interview discussing the use of the wok, American chef Kenji López-Alt asserts, “The techniques that you use [a tool] for come after the tool, as opposed to it being a tool that was designed for one specific technique.” His words are a cunning explanation for how cooking and eating methods have shifted and splintered through time, suggesting that approaches to food today are the result of contextual shifts in the ether of the past. He offers also the striking reminder that tools, and thereby ways of eating are not bound to the understandings we have of them today.

The introduction of rice bowls in the Chinese Han dynasty radically altered the structure of the Chinese aristocratic meal. Until then, rice was traditionally eaten seated on the floor out of a large communal pot, from which participants would take portions with their hands. The new individual rice bowl made it sensible to shovel rice into the mouth, using chopsticks instead of hands. Until then, chopsticks had been used solely for plucking bits of meat and vegetables and also for cooking––never for rice. With the introduction of the rice bowl their function completely pivoted and the entire structure and norms around the meal itself changed forever. Had the rice bowl never been introduced, perhaps Chinese contextual meals would have retained the involvement of the hands.

Within the traditions of India, the continued practice of eating with hands stems from ancient Vedic philosophy. According to the Vedas there are specific mudras, or shapes formed by the hands and fingers, put to significant use in prayer and dance and also in daily meals. There are mudras for eating slender foods, for adding spice to a recipe, for holding a piece of uncut fruit. Rice is gathered with the ghronikah mudra, where the fingers come together like the pedals of a flower. Vedic science understands that when eating by hand, digestion can actually begin before nourishment reaches the mouth. By breaking down food with the fingers, not only is the stress of oral and internal digestion assuaged, but the senses are heightened, the fire of digestion kindling as the body prepares itself for the meal to come.

If you were to ask why someone was using chopsticks or eating a meal with their fingers, would Han dynastic tradition or Vedic science be credited? Probably not. It would be something like asking an American why they curl spaghetti around their fork––Americans will be surprised to learn that spaghetti was commonly eaten with the hands in Naples until the 20th century. Because the fresh sea air and sunlight of Naples dried pasta effectively, the noodles were cooked in the street and enjoyed from the fist. The practice waned with advancements in indoor pasta-drying technologies.

Repeated over generations, the smallest ritual gestures become habitual, and habits, nature; the fish does not consider the water it swims in. Through perpetual use of a tool in a certain light, their past functions can be easily forgotten. Consider our human hands. Hands and their opposable thumbs began as functional gripping mechanisms for branches and nourishment, and slowly shifted overtime to grasp pestle and club. Today hands are called upon to conduct surgeries, comb hair casually, write good and bad poetry, engage pixelated realities; our modern context begs modern applications for these gripping extremities of such humble origins.

And tools need not be tangible in order to change with the iterations of time and space: language as tool for communication is constantly evolving; meanings and functions of words in languages around the world have strayed remarkably from their original etymologies: slang emerges; words are shortened or reemphasized, reinvented. James Baldwin wrote that the root function of language is to control the world by describing it. Is the root function of all tools not to control the world by testing it, communicating with it?

Every single man-made tool has been created to address some issue, however big or small, for which it alone is the solution. They evolve or become obsolete according to time and space. If an available tool is used effectively, keep using it for that purpose. If not, time to seek out a different tool, a different approach, give up on that specific affair, etc. The entire time, the tool is saying something about itself, about the abilities of the user, about the substance that tool and user are effecting, speaking loudly or softly about the nature of reality.

Tools are telling us something of significance, always, in a language that is perhaps easily unacknowledged. Anyone who drives over a bumpy dirt road is in some way in communion with both their vehicle and with the uncertain grade of the road itself. If we were to feel that same road with the soles of our shoes, there would be different concerns on our mind. If, year after year, we were to prefer one mode of transportation over an alternative, our understanding of that journey would be unquestionably unique.

The approaches we take with the tools at our disposal indelibly change our relationship to the thing itself. There are many reasons why the taste and ultimate perception of one meal might differ between two people, or between the same person on different days; even the intensity of the sun or the presence of rain play a role in this. Singapore hosts diverse and diverging relationships with the act of eating; memories of the way grandmothers used to cook, a nostalgia for certain spices and an aversion toward others.

Hands convey greetings and farewells and insults and fidelity. But when one sees another hand diving into a pile of rice and knows that gesture as familiar, that too is communication, however inadvertent. Recognising one another and finding people legible is an essential component of the social experience, especially amidst immense cultural crossroads. To eat by hand has been to know something of the man crushing idli in his fingers across from me.

When I choose to engage a meal by hand I’m heading toward an outcome that might be quite similar to my neighbour who wields the fork and spoon, and yet our impressions of that meal will not be the same. By listening to what my fingers are saying as they themselves cradle bites of food, a distant fondness for my abilities and daily meals has surfaced, or resurfaced. If I continue to eat this way for years I imagine it would become second nature, another gesture in the daily routine. But in this moment, I glow in the small expanse of my powers.

~

Jackson Kao is an American researcher living in Singapore, conducting photojournalism and ethnography on local food culture. His coffee order is kopi-o-kosong (black coffee without sugar).