RE-ENVISION: Pickles (Sweet & Sour Power: What’s the Big Dill)

By Frankie Jenner

RE-ENVISION is an ongoing series of crossroads research memos produced by our associates at Appetite. We trace the cultural genealogies of food from around the world to challenge commonly held beliefs about origin and authenticity.

Pickles. What comes to mind?

In England, the word conjures images of the murky brown, Branston original pickle jar, or perhaps the vibrant golden sheen of piccalilli, a mustard pickle. Half-full glass jars accumulate on fridge shelves, brimming with brines and bubbling ferments: our secret culinary weapon. They can salvage any dish by imparting tang, sweetness, spice, tartness, packing a sour punch or even subtle buttery suggestions.

The history of pickles and pickling

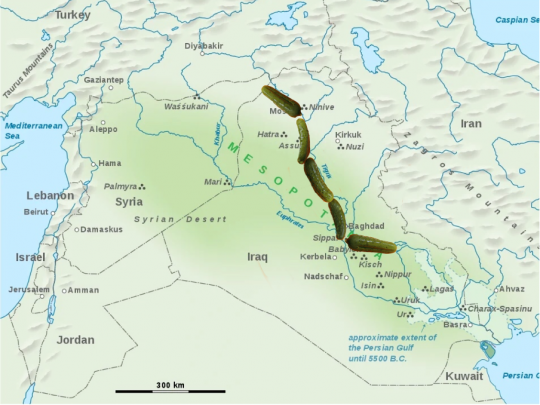

The history of these jars reaches further back than the depths of our fridges. According to archaeologists, pickles first graced us with their sumptuous beauty in 2400 BC, in Ancient Mesopotamia. This was the fertile plain situated between the Tigris and Euphrates river, in what is now collectively referred to as the geographical region of Iraq, Kuwait and Syria. Its stable climate had rich soil and a reliant supply of fresh water. It therefore comes as no surprise that cucumbers, native to India, were brought to the region several centuries later, to begin a pickling tradition in the Tigris Valley.1

Map of Ancient Mespotamia. It’s fertile plane is highlighted in green, spanning across modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey and Syria. Source: Adapted from Goran tek-en/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

Aristotle claimed they had healing properties, Cleopatra insisted they were responsible for her good looks, Julius Caesar fed them to his troops to strengthen them for battle and the Torah records that when the Jews were liberated from Egypt, they yearned for the cucumbers they used to pickle.2 Whilst many of the earliest records of pickles concern the cucumber, as the pickling technique migrated across different geographical and cultural boundaries, we begin to see an expansion of the foods being pickled.

Broadly speaking, there are two different types of pickles: vinegar and lacto-fermented. The former pickles by adding vinegar to the product in order to preserve through the application of acid. Take the Original Branston Pickle as an example: the assortment of diced vegetables are submerged in a vinegar based sauce, in order to preserve their shelf life. The latter form of pickling adds salt to the food, which in turn, draws out their liquids and a chemical reaction then converts some of the sugars and other aminos within the liquid, into a lactic acid. It is this lactic acid that then pickles the products and ultimately preserves them. Sauerkraut, kimchi, kosher dill pickles and daikon pickles, amongst countless others, are examples of a fermented pickle.

Therefore, the goal is often similar for both vinegar-based and lacto-fermented pickling: to preserve a specific food product(s). Vinegar pickling achieves this by submerging the food into an already acidulated liquid: vinegar. Whereas lacto-fermented pickling produces lactic acid through the addition of salt, which ultimately drives the pickling process. Essentially, most fermented foods are pickled, but not all pickles are fermented.

Lotsa Different Pickles! Source: Frankie Jenner

The language of fermentation

I am specifically interested in exploring the fermented form of pickling, and how this phenomenon which is seemingly situated within the culinary sphere, can actually teach us a lot about social history. Yes, you did read that right. I want to look at how pickles are actually a tool for understanding more about history. Here at Appetite, we have written specifically about the history of fermentation as a food process; Thomas Martinez has traced the origins of kimchi and natural wines, Margot Richter has explored the development of sourdough and the Appetite team has written about India’s Achar pickle.3 If you are intrigued about fermentation’s origins, I point you towards their work. As for now, I am concerned more about the etymology of fermentation: its linguistic development over both time and place.

The etymology of the word ‘fermentation’ predates our scientific understanding of the word. People have been fermenting food for thousands of years, but it is only since the late 19th century that it has been an actual term associated with microorganisms.4 Prior to this, fermentation was used in the English language to refer to a period of excitement, agitation, unrest, innovation, capacity for change or just a general, metaphorical ‘bubbling’ within society. This is because fermentation comes from the Latin word ‘fervere’: to boil. History has witnessed a multitude of ferments, from religious, to philosophical, political, musical and even mystical. As such, there is a shared language between social history and science that is inherent to the etymology of the word ‘ferment’.

Fermentation as metaphor

Beyond its scientific and linguistic complications, fermentation can therefore be used as a lens to deeper explore our social history. Fermentation does not just belong in a jar on your kitchen shelf. Fermentation is a metaphor. This is an idea that has recently been explored in greater depth by Sandor Ellix Katz, a fermentation revivalist and author of Fermentation as Metaphor. Katz is a notorious figure amongst the loose collective of fermentation enthusiasts and experts who celebrate, teach, research and sell fermented products, to a predominantly Western market. Their work is a reflection of our times, where a recent boom in the Fermented Foods Industry is predicted to be worth $690 billion by 2023, in the West alone.5 While Katz’s application and development of the methodology are interesting, his ideas are not new. Fermentation has long existed as a metaphor, prior to its scientific understanding.

To unravel its metaphorical significance, we can turn to the processes involved in making a lacto-fermented pickle. It is a process that involves cramming, submerging, adding salt, mashing together various and often disparate shreds, breaking down and letting them sit, nestled amongst one another for a duration of time, long enough to see a transformation, a progression and ultimately some visible activity. It is akin to the ways in which societies have been formed: through the assimilation of different peoples, cultures, traditions, languages, religions and opinions. In the context of anthropology, assimilation refers to the process in which individuals or different ethnic groups are absorbed into the dominant culture of society.

The different foods that are fermented and pickled are comparable to those being assimilated. The salt is a binder, in the same way that communities bind people. They both encourage one another to release and expose themselves to their immediate neighbours. This assimilation is not always natural. Assimilation is often forced. Amongst countless examples, we can identify the forced assimilation of the indigenous peoples in the European colonial empires, the forced assimilation of the Chinese in Bangkok by the Siam government during World War One, the forced assimilation of the African diaspora as a result of the trade of enslaved people and even the forced assimilation of refugees imposed by both localised and government authorities.

As a result, assimilation is not always successful, especially when it is forced. History has shown that it often leads to further conflict and struggle. In the same way, lacto-fermentation is not always successful. Sometimes the errors are salvageable and can be remedied. But other times, they have passed a point of no return; they begin to give off a foul smell and hairy mould begins to settle on its surface, requiring it be binned. There is a vast language shared between lacto-fermentation and societies; it lies in the myriad of ways they are formed, progress, conflict, breakdown, preserve tradition, are ‘saved’ (there is always a politics to ‘saving’ something or someone) and ultimately, how can also be wiped out, destroyed, cancelled and forgotten.

Fermentation and the fear of bacteria

Assimilation naturally fosters an environment of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. This is a dynamic that we can also identify in both fermentation and social history. Western society is obsessed with fighting microbes. Since the first connections were made between bacteria and disease by Semmelweis’ hand washing standards, Pasteur’s Germ Theory and Lister’s promotion of aseptic surgery in the 19th century, bacteria has been regarded as evil… and therefore must be neutralised accordingly.6 Penicillin, chlorinated water, antibacterial soaps and fabrics, kitchen disinfectants, bleach, face masks and air purifiers. This is the war on bacteria. Bacteria is increasingly associated with death, disease, illness and danger. These associations have been drastically heightened over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic and big industry increasingly capitalises on our innate fear of the potential of bacteria.

The War on Bacteria. Source: Frankie Jenner

As such, the cultivation of bacteria within the fermentation process has led many, predominantly in the West, to approach it with trepidation. It is often regarded as dangerous and risky. The fermentation ecosystem is littered with articles, videos and publications that chronicle how fermented foods can cause serious harm to your health, increasing the risk of botulism, and other forms of pathological viruses and bacteria resulting from ferments ‘gone wrong’. As such, the language that surrounds fermentation is loaded with terms such as sterile environments, purity, contamination, spoiling, toxicity, prevention of bad bacteria and promoting good bacteria. The same language is used across societies to differentiate between ‘us’ and ‘them’. We see this in the widespread association of Covid-19 with people of Chinese ethnic heritage, leading to a drastic increase in racially motivated hate crimes; the global response to the Black Lives Matter movement and the way in which the West looks down upon, or turns away from the Global South. Social history and the process of fermentation generally fear the unknown and the ‘other’.

Both instances illustrate the curation of fear within modern society. The word ‘curation’ is very conscious here, as it implies agency amidst a social construct. To ‘cure’ is the process of removing moisture and further preserving structures from noxious bacteria, through the application of salt. Curing in health and curing in cooking have the same root. Just as bacteria cultivate during fermentation, the curators of our societies also cultivate fear. When persistent, this fear will inevitably spread and start to permeate throughout various social circles and movements. Agency lies with authorial figures: they are the curators.

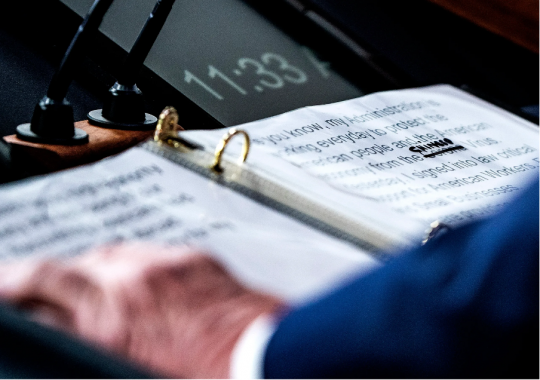

Take the increasing association of Covid-19 with people of Chinese ethnic heritage; this can largely be traced back to the agency of former US President Trump’s rhetoric during the early stages of the pandemic. In March 2020, Trump first used the term ‘China Virus’ within a Tweet to refer to the spread of Covid-19. By attaching a geographical location and ethnicity to an unrestricted disease, Trump fuelled what has been described as a ‘tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering’.7 A different kind of virus began to spread: no longer bacterial, Trump curated a virus of fear and hate.

The permeation of this particular kind of fear spread quickly. We began to see other world leaders adopt this language of fear: in a Tweet, Brazil’s education minister referred to the pandemic as part of China’s ‘plan for world domination’; likewise, an Italian governor asserted the country would be better equipped to handle the virus than China, since ‘we have all seen the Chinese eating mice alive’.8 This culture of fear filtered down within society. Initially, we began to see a rise of Anti-Asian hashtags on social media platforms such as Twitter. But this quickly extended beyond the internet and began to physically infiltrate: levels of anti-Asian hate crimes and violence soared, internationally.

During a briefing to the White House in March 2020, a photographer captured former President Trump’s notes on his speech which addressed the pandemic. The word ‘Corona’ has been crossed out with a black marker and replaced with the word ‘Chinese’. Source: Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post

When we think back to the language surrounding fermentation, we can identify many parallels amongst the shockwaves that Trump initiated. Many responders were motivated by an innate fear that people of Chinese ethnic heritage were supposedly contaminated, impure, spoiled and dangerous. Just as fermenters often fear this happening to their food, society adopts a similar fear: contamination of the ‘self’, by the ‘other’. The overarching tie between these two kinds of fear is irrationality. In much of Katz’s work, he tries to tackle the myth that fermentation is dangerous. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there has never been a documented case of food poisoning from fermented vegetables.9 None of the supposedly ‘bad’ bacteria can survive within a lactic acid environment. Bacteria form an essential part of our physiological makeup as our digestive tract is teeming with around 100 trillion bacteria and other microorganisms, as such, the consumption of fermented foods is crucial for the development of the gut’s microbiome.10 These developments illustrate how fear is both curated by agents, and disseminated amongst society: its breeding ground.

More than just a pickle

Currently, these ideas are largely theoretical, abstracted and grounded in the etymology of fermented pickling. In the following installation of this series, these ideas will be grounded in art. Here at Appetite, we actively pursue a crossroads approach to food, looking beyond its initial domain and connecting it to a larger system of interrelated and interdependent parts.

A lacto-fermented pickle is more than a cucumber, radish or egg sitting in a jar. It is more than just a food-type. Pickles are a lens through which we can understand the world, its tensions, conflicts and ultimate developments. If you enjoyed this piece, keep an eye out for the next installation which will be applying many of these ideas to Pickle Politics: the accumulation of a lengthy research cycle by the artistic collective Slavs and Tatars.

Footnotes

1Sarah Pruitt, “The Juicy, 4,000-Year History of Pickles’, History, last updated August 7, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/pickles-history-timeline.

2Ibid.

3Thomas Martinez, “RE-ENVISION: Kimchi”, Appetite, Accessed on September 10, 2021. https://research.appetitesg.com/idea/re-envision-kimchi/; Thomas Martinez, “RE-PRESENT: Natural Wines”, Appetite, Accessed on September 10, 2021; https://research.appetitesg.com/idea/re-present-natural-wines/; Margot Richter, “RE:ENVISION: Sourdough”, Appetite, Accessed on September 10, 2021. https://research.appetitesg.com/idea/re-envision-sourdough/; “Etymological origins of the ‘achar pickle’”, Appetite, Accessed on September 10, 2021. https://research.appetitesg.com/idea/etymological-origins-of-the-achar-pickle/.

4‘Live Stream with Sandor Katz’, YouTube Video, 51:05, posted by ‘TatteredCover’, November 10, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0X0q8vgAABk.

5Miin Chan, “Lost in the Brine”, Eater, March 1, 2021. https://www.eater.com/2021/3/1/22214044/fermented-foods-industry-whiteness-kimchi-miso-kombucha.

6Holly Ahern, Microbiology: A Laboratory Experience (State University of New York Oer Services, 2018), https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/suny-microbiology-lab/chapter/the-war-on-germs/.

7“Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide”, Human Rights Watch, Accessed on December 12, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide.

8Ibid.

9Hirsch, Diane Wright. “Fermentation: Preservation with Benefits”, University of Connecticut Extension News, Accessed on December 18 2021. https://news.extension.uconn.edu/2015/11/20/fermentation-preservation-with-benefits/.

10“Fermented foods can add depth to your diet”, Harvard Health Publishing, Accessed on December 13, 2021, https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/fermented-foods-can-add-depth-to-your-diet.

Notes

Annotated Bibliography

Miin Chan, “Lost in the Brine”, Eater, March 1, 2021. https://www.eater.com/2021/3/1/22214044/fermented-foods-industry-whiteness-kimchi-miso-kombucha

In this article, Miin Chan addresses the Western commercialisation of fermentation; an industry that’s roots are firmly planted in East Asian traditions. Chan critiques the whiteness of the industry’s leading figures, including Sandor Katz. As a member of the fermentation community herself, Chan offers a poignant insight into the transformation of the fermentation industry from her childhood in Malaysia during the 1980s, through to her present-day occupation as a Wild Fermentactivist Gastronomer based in Melbourne. Chan highlights the importance of promoting a diverse study of ferments, providing recognition for their complex histories and sociocultural significance. This is a really insightful article into understanding the whitewashing of fermentation, in Chan’s own words: ‘The fermentation industry, like any other, has a whiteness problem.’

Sarah Pruitt, “The Juicy, 4,000-Year History of Pickles’, History, last updated August 7, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/pickles-history-timeline

Sarah Pruitt manages to succinctly capture the 4,000 year-long history of pickles, from the ancient world, through to the modern-day. Whilst the exact origins of the process are largely unknown to many archaeologists, Pruitt begins her account from c. 24000 B.C. in ancient Mesopotamia.

“Etymological origins of the ‘achar pickle’”, Appetite, Accessed on September 10, 2021. https://research.appetitesg.com/idea/etymological-origins-of-the-achar-pickle/

As part of our broader work here at Appetite on pickling, this article traverses the etymological origins of the infamous ‘Achar pickle’, also originating in the Tigris Valley in India. The pickling agents of the Achar pickle vary widely, from brine, oil, vinegar and even fermented palm toddy.

Further Reading

Katz, Sandor. Fermentation as Metaphor (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2020)

Sandor Katz is a prominent fermentation revivalist who seeks to demystify the process of fermentation in order to make it more accessible, with the hope to decentralise the system of food production: an act of reclamation. This is Katz’s fourth publication on fermentation, in which he has taken a much more philosophical approach to the process, drawing comparisons between the biological and metaphorical uses of the word.

Zilber, David. “Fermenting Culture. An Interview with David Zilber” Interview with Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, Emergence Magazine. Podcast audio, October 7, 2019. https://emergencemagazine.org/interview/fermenting-culture/

David Zilber is the former director of the fermentation lab at Noma, in Copenhagen, Denmark. In this incredible interview with Emmy nominated filmmaker and composer, Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, the pair discuss the parallels between food and culture. Zilber remarks that ‘“Culture” and ‘culture’ mean two different things to a biologist and an anthropologist, but in fermentation, they overlap completely.’ The fermentation lab planted its roots in the Nordic tradition of preservation, such as capers and saltfisk, which is dried and salted cod. Throughout the interview, Zilber comments on the parallel developments between fermentation and agriculture as a deeply embedded cultural and historical relationship: one that informs how people relate to both place and culture more broadly.

iron.saint, “Food & Culture and Claude Levi-Strauss”, Sturm und Drang, July 26, 2012. https://fermentationculture.wordpress.com/2012/07/26/food-culture-and-claude-levi-strauss/

If interested in the historical associations between fermentation and culture, refer to the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss. He was a prolific French anthropologist and ethnologist working predominantly throughout the 20th century. In one of his seminal works, The Raw and the Cooked (1964), Lévi-Strauss characterises food as a lens through which to understand social history. He separates food into three primary forms: raw, cooked and rotted. As such, fermentation is situated within the rotted category. In this article, iron.saint manages to capture the essence of Lévi-Strauss’s model: ‘That it was the fermentation of natural substances into something transformative and slightly mind altering, that ushered in our human development of culture.’